Abel’s Cry for Vengeance on Cain

(1 Enoch 22:5-7)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

The biblical narrative underlying this painting is the narrative concerning Cain and Abel in Genesis 4.63 Adam and Eve had two sons, first Cain and then Abel. Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground. Cain brought an offering of the fruit of the earth to the Lord, while Abel brought of the firstlings of his flock and of their fat portions. For an unstated reason, the Lord approved of Abel and his offering, but disapproved of Cain and his offering. So Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell. The Lord asked Cain, ‘Why are you angry, and why has your countenance fallen?,’ and then said, ‘If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is crouching at the door; its desire is for you, but you must master it.’ Cain’s reaction to this message, which implied he had not done well, was emphatically negative:

Cain said to Abel his brother, ‘Let us go out to the field.’ And when they were in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel, and killed him (Gen 4:8)

So the Lord asked Cain, ‘Where is Abel your brother?’ and Cain replied with a lie, ‘I do not know; am I my brother's keeper?’ This response elicited the following response from God:

‘What have you done? The voice of your brother's blood is crying to me from the ground. And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it shall no longer yield to you its strength; you shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth’ (Gen 4:10-12; RSV).

Cain replied to God that, as a fugitive and wanderer upon the earth, anyone who found him could slay him. But God rejected this: ‘Then the Lord said to him, “Not so! If any one slays Cain, vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold.” And the Lord put a mark on Cain, lest any who came upon him should kill him’ (4:15). Cain did indeed survive, married and fathered a son and this was the beginning of Cain’s numerous descendants (4:16-24). At some point he must have died, but Genesis does not say when or how. Meanwhile, Adam and Eve had another son, Seth, and enjoyed a numerous lineage through him, of which one was Enoch, in the sixth generation after Adam.

1 Enoch contains a succinct reference to this narrative of Cain and Abel (22:5-7). At this point in Enoch’s wandering through the cosmos his guides are the archangel Raphael and other holy angels. They travel to a place where the angels show Enoch a high mountain in the west. It contains four hollow places, three of which are dark and one illuminated. Raphael explains to Enoch that these hollows were created for the souls of the dead to be kept in until the day of the great judgment (22:1-4). This picture of the souls in pits on a mountain is sharply differentiated from the usual Israelite understanding of the dead being in Sheol below the earth (see 1 Samuel 28). At this point Enoch observes as follows:

There I saw the spirit of a dead man making suit, and his lamentation went up to heaven and cried and made suit. Then I asked Raphael, the Watcher and the holy one who was with me, and said to him, ‘This spirit that makes suit—whose is it—that thus his lamentation goes up and makes suit unto heaven?’ And he answered me and said, ‘This is the spirit that went forth from Abel, whom Cain his brother murdered. And Abel makes accusation against him until his posterity perishes from the face of the earth, and his posterity is obliterated from the posterity of human beings’ (22:5-7).64

While the connection with Gen 4:10 is apparent, in Genesis it is Abel’s blood (animate and personified) that calls to God from the ground, whereas in 1 Enoch 22:5 Abel’s spirit does so. The difference probably represents changing Israelite views on the nature of the human person from the earlier time when Genesis was written to the Hellenistic period of origin of 1 Enoch 1-36. That the spirit of Abel is making suit to heaven connects this incident with other examples of petitions that are directed to heaven: such as that by the earth in response to the violence of the Giants (7:6; 9:2), by human beings in consequence of the knowledge taught by the Watchers (8:4) and by the rebellious Watchers seeking mercy from God (13:6-7). The language of petition comes from the administrative practices of ancient Near Eastern and Hellenistic monarchies where subjects of the king wrote to the king or his courtiers requesting that they help them with their problems. The very language of the numerous petitions in Greek that have survived in the sands of Egypt is found in the extant Greek text of 1 Enoch 1-36.65 This language is part of the evidence that heaven in the text is modelled on the ancient royal court and its courtiers, not on the Jerusalem Temple and its priests.

The implications of the accusation by Abel’s spirit are intriguing. Certainly the fact that Abel’s spirit makes the accusation imputes to him knowledge that Cain did, indeed, have descendants (as noted above). Yet is Abel asking (God in) heaven to hurry along the death of Cain’s posterity, or is he simply complaining about Cain until such time, presumably the End-time, when his descendants will have been obliterated from the earth? Most probably the former is intended. Abel’s spirit is directing a petition to heaven and that means asking God to do something, which here can only be to wipe out Cain’s descendants. Given that Genesis shows God to be surprisingly solicitous in preserving Cain’s life, it is rather surprising to find Abel asking for the opposite fate to be inflicted on his descendants. But that is what the text implies. Whether this constitutes a request for vengeance or justice is, however, a more difficult question. Neither word, ‘justice,’ nor ‘vengeance’ appears in the passage. One’s initial reaction might be that it is grossly disproportionate to call for the death of all Cain’s descendants when only Abel himself was killed. But Abel’s implied concern is that Cain’s murdering him deprived him of the posterity that Cain had himself enjoyed and that it would therefore be just for Cain’s posterity to be removed from the earth as well. For this would put them both in a roughly equal position. So perhaps Abel’s spirit is calling for justice rather than vengeance (even though there may be times when they are hard to distinguish). Therefore, we have here a highly imaginative literary and theological interpretation of the circumstance that Cain had descendants, refracted through the sense of grievance felt by Abel’s spirit.

Finally, and most importantly, this comparatively brief reworking of the story of Cain and Abel in 1 Enoch 22 serves to alert us to something of fundamental importance for how the Enochic scribes understood evil.66 This is that the root of evil in the world is violence. To appreciate this we need to recognise how 1 Enoch 1-36 distinguishes between ‘narrative time,’ meaning the broad sweep of time implied in the text (beginning with the creation in Genesis and proceeding to the End), and ‘dramatic time’, which is the more specific period within narrative time within which the major events of the plot take place.67 Whereas within dramatic time evil begins with the defection of the Watchers to earth and the mischief they wreak there (1 Enoch 6-7), the text makes clear that, within the more encompassing framework of narrative time, evil, epitomised by violence, began on earth much earlier with Cain’s violent murder of his brother and was entirely human in origin (even though this homicide is not mentioned till 1 Enoch 22:5-7).

The importance of the story of Cain and Abel to the Enochic scribes in relation to the question of evil emerges when we consider how they dealt with the Genesis account of Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden. Later in his wanderings Enoch arrives at a place in the east where the paradise of righteousness is located, which contains many beautiful trees (1 Enoch 28:1-33:4). One of them, ‘the tree of wisdom, whose fruit the holy ones eat and learn great wisdom’, is particularly beautiful and Enoch asks his angel guide about it. Then Raphael, the holy angel who was with him, replies as follows:

‘This is the tree of wisdom from which your father of old and your mother of old, who were before you, ate and learned wisdom. And their eyes were opened, and they knew that they were naked, and they were driven from the garden’ (32:6).

There is nothing here about the disobedience of Adam and Eve, nor about their being punished for it by dying or becoming mortal. The text imputes a measure of incongruity in what they had done—eating food that was not meant for them and thus meriting their expulsion from the garden—but they are not described as having sinned. Accordingly, as far as the author or authors were concerned, the first human sin was Cain’s murder of Abel, an act of violence. This is the major point here, the first instance of evil on the earth, a theme that will be taken up repeatedly and developed across the entirety of 1 Enoch. Other explanations, such as that Abel is the prototype of the righteous martyr,68 miss the role of this incident within the larger narrative presupposed in the text. Throughout 1 Enoch violence figures as the primary sin and this is where it begins.69 Yet this is also the first instance of anyone dying in the larger narrative presupposed in the text, and this raises the admittedly daring question of whether the Enochic scribes regarded this incident as the cause of humans losing their initial immortality.

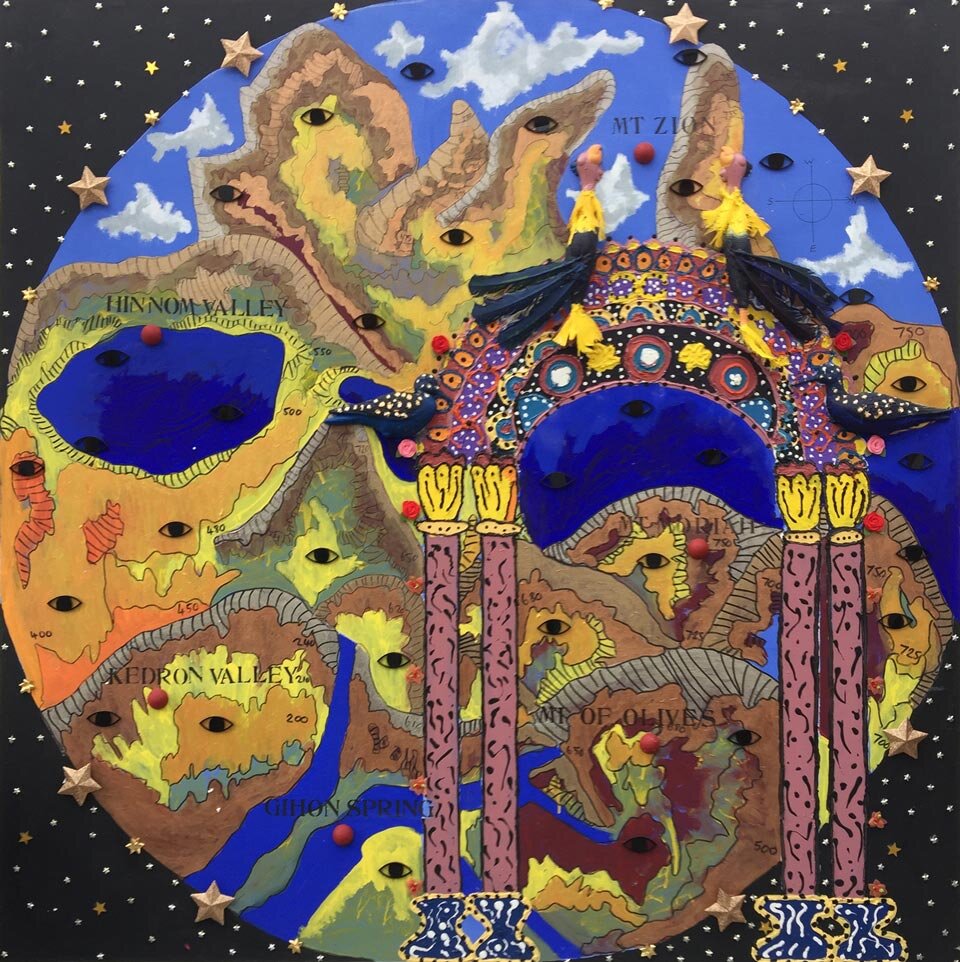

In the next painting, Abel’s Cry for Vengeance on Cain (1 Enoch 22:5-7), violence is central in that it contains a multi-layered dialogue that explores the circumstances surrounding the first fratricide. The artist invites the viewer to imagine the scream coming from an entrapped man as he responds to an unjust and violent death: it can send shivers down our spine. What if everyone who has ever been wronged screams for justice for eternity? Maybe this is the noise we hear when no worldly sounds are blocking the airwaves. When all else is silent, in a world pervasively infected by evil, is this what we hear?

In this painting the artist has created an almost cinematic effect where the viewer is confronted by the ‘before-and-after’ scenario of the crime story. He calls on the audience to think about the questions posed by the painting—of original sin, of vengeance, of justice and injustice. What was going through Cain's mind? He invites the audience to absorb the issues here, after reading the text of 1 Enoch 22:5-7, and to draw their own conclusions. As viewers, they are being given a role and a voice, as with the confessional altarpieces of the fifteenth century.

In dialogue with Philip Esler and his views on the Enochic understanding of the origins of sin (summarized above), the artist has created this work based on the duality of human beings and the divided self. In its upper hemisphere the painting contains two imprints of the same person, of their left and right sides, which create the effect of a Rorschach test. The aim is to show how the two sides of a human being can love and hate at the same time. The artist has also sought to capture the moment just before the fatal attack in order to examine the intent to kill. If Cain planned to kill Abel in the field, then this act was indeed murder. Yet through the painting the artist seeks to explore and understand the mind-set of Cain before he acts out this scenario. A sharp, jagged flint lies in wait on Cain’s side of the painting. Was it placed there, ready to use or was it grabbed in the heat of the moment? On Abel’s side there are two sheep skulls predicting his fate, as in the vanitas paintings of the Dutch period by artists such as Antonio de Salgado and Pieter Claus. Death awaits him. However, these sheep have a dual significance as they also represent the ancient Nagar, the mysterious End-time creature of 1 Enoch 90:38 mentioned above. All of this visual information serves to interpret Enoch watching and scribing this ominous event and Abel’s cry.

The gifts offered by Cain and Abel mentioned in Genesis feature prominently in the painting. Stretching through its upper and lower hemispheres is a large sheep carcass: this is the offering Abel that gives to God as a token of showing his prosperity and the potential to develop and maintain a large civilisation. In the painting’s lower left quadrant, Cain's corn offerings are in place, as are his—in this depiction— Ethiopian baskets but the maggots in the pile of overripe apples predict that this will be a failed offering.

There are flowers growing in the garden. Abel’s flowers show the green shoots of life, while Cain’s are black and red to represent the blood about to be spilt and to flow into the earth forever. The two yellow suns at the top and bottom of the painting represent life and death. The orange, and no longer yellow, sun signifies God’s disappointment and the transition of Cain to sinfulness and mortality. Ultimately (and here the artist takes a bold leap away from blaming Adam and Eve for human mortality) death will be the fate of us all, now that immortality has been taken from humanity as a result of this sin.

As well as being replete with symbols and metaphors based on this event as described in 1 Enoch 22, the entire painting owes its debt to Ethiopia. This is evident in the facial features painted in Ethiopian style and in the palette and colours applied to the canvas. This latter dimension is very evident in the horizontal bands in the painting in colours very common in Ethiopian painting: from the top down we have: the gold of heaven; the blue of the sky; the white band of the firmament, separating the heavenly realms and earth; the khaki-green of the flora; the brown of the earth and the red of hell. The replication of the gold spheres at the very top and very bottom of the painting speak to God’s control of the cosmos, from heaven to hell. The painting also pays homage to fundamental characteristics of Ethiopian art in other ways: the use of silhouette, the heavy employment of outlines and the practice of storytelling through colour and form. The stars in the circle are wooden (signifying how they first looked to human viewers), but those in the celestial space, in consequence of Cain’s act, are blackened because of what they are witnessing.

The whole scene is acted out as if in a celestial play. The spotlight falls on the momentous act as it is witnessed by the whole universe and, of course, by God. This is the moment when everything changes for humanity. Abel’s anguished cry for justice rises up to the heavens like an anti-annunciation. This infamous moment is sacred but tragic too. It is the road map of our humanity. We all have a choice; how will we use it? Ultimately, the painting is asking what, in the aftermath of the first sin—which in this view was violence—will be the consequences for humankind?

On to the next painting?

The Tree for the Righteous at the End-Time

__

63 The discussion of this painting is gratefully reproduced by permission of the Biblical Theology Bulletin, Volume 50:3 (August 2020), 136-153, in an article entitled 'Painting 1 Enoch: Biblical Interpretation, Theology, and Artistic Practice', by Philip Esler and Angus Pryor.

64 Translation Nickelsburg and VanderKam 2012: 42-43, slightly modified.

65 Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers, 72-78.

66 See Esler’s essay, ‘Deus Victor’.

67 See Esler, Ibid., 168-170.

68 Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch, 306.

69 Esler, ‘Deus Victor’, 168-175.