Enoch’s Transformation Before the Angels and God

(1 Enoch 71:11)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

The second part of 1 Enoch, ‘The Book of Parables’, comprises Chapters 37-71 and was one of the last sections of the text to be written, probably in the first century BCE. Much of the Book of Parables provides a different slant on issues prominent in 1 Enoch 1-36, such as the goings on in God’s heavenly court, his ultimate vindication of the righteous, the punishment of the wicked (angels and human beings), astronomical information (especially Chapter 59), references to Enoch and his journeys (Chapters 52-54; 57; 66; 67:4-8 and 11-12), and material concerning Noah and the flood (especially Chapters 65; 67) and on the fallen angels (Chapter 69).

An important theme is introduced in Chapter 48 when a figure called ‘the Son of Man’ appears:

And in that hour that Son of Man was named in the presence of the Lord of Spirits, and his name, before the Head of Days. Even before the sun and the constellations were created, before the stars of heaven were made, his name was named before the Lord of Spirits (48:2-3).

He will be a staff to the righteous and for that reason he was chosen and hidden in God’s presence before the creation of the world (48:4, 6; 62:7). The kings of the earth will worship him and petition him (unsuccessfully) for mercy (62.9; 63), while the righteous will eat with him (62:13). He is also referred to as ‘his Anointed One’ (48:10) and the ‘Chosen One’ (49:2, 4; 51:3, 5; 55:4; 61:8, 10; 62:1) in whom dwells wisdom and insight (49:3) and who will judge the things that are secret (49:4).

In the conclusion to the Book of Parables Enoch is the subject of a remarkable transformation, when he is identified as the Son of Man (71:14). The relevant description, occupying Chapters 70-71, begins with a retelling of Enoch’s ascent to heaven, briefly mentioned in Gen 5:24 (‘Enoch walked with God; and he was not, for God took him.’) and developed very fully in 1 Enoch 14. This section of the text (70:1-12) begins with Enoch’s being lifted up, while still living, ‘into the presence of that Son of Man and into the presence of the Lord of Spirits’ (70:1-2). Although the Son of Man is mentioned here in a way that suggests he is a different figure from Enoch, there is another way to explain the text (to be discussed below). After that Enoch is taken on a tour of the cosmos (70:3) and reaches the heavenly palace, witnessing its paradoxical mixture of ice and fire and angels (God’s heavenly courtiers) going in and out (70:5-8). Then God and his angels emerge from the palace (70:9-10), at which Enoch informs us that

I fell on my face, and my flesh melted, and my spirit was transformed (71:11).

While the motif of Enoch’s falling on his face is repeated from 1 Enoch 14:24, there is nothing like this ensuing transformation in 1 Enoch 14. For this proves merely to be a prelude for the next step, when God comes to him and says:

You (are) that Son of Man who was born for righteousness, and righteousness dwells on you, and the righteousness of the Head of Days will not forsake you (71:14).

This verse has been a source of considerable debate.88 How could Enoch suddenly be identified with the Son of Man? R. H. Charles, an eminent scholar from early in the last century, was so troubled by this that he (notoriously) altered the text (for which there is zero support in the textual tradition) to read ‘This is that Son of Man’, so that Enoch was being shown someone separate from himself. A major question that arises is this: if the Son of Man is identified the Enoch, where does that leave Jesus Christ, who is repeatedly referred to as the Son of Man in the Synoptic Gospels. It has been suggested that 71:14 is a later, Jewish addition to the text aimed at making this precise point, that Enoch not Jesus is the Son of Man and hence Messiah. But both of these are rather desperate suggestions. Various solutions to the problem have been proffered, of which three deserve close attention.

Firstly, according to T. W. Manson:

Enoch incarnates, not a ‘pre-existent heavenly being’ but a divine idea. He is hailed by God as the incarnation of the idea, after he has lived a life of righteousness on earth. He becomes the first actualisation in history of the Son of Man idea and the nucleus of the group of the elect and righteous. Some of these have died and are with Enoch in Paradise; others are still militantes in saeculo. The thing for which all wait is the manifestation of the Son of Man idea in triumph in the Messianic vindication of the elect and righteous.89

This was in line with Manson’s broad (and plausible) view that ‘I cannot help thinking that one object of the apocalyptic writers was to justify God's ways to man by making a sensible story of the whole course of history.’ 90

Secondly, James VanderKam offered a somewhat similar and very appealing suggestion to the problem in 1992:

What the author appears to have intended in 70:1 was that Enoch's name was elevated to the place where those characters whom he had seen in his visions were to be found, namely in the throne room of the celestial palace. That is, he does not see the son of man here but begins his ascent to the place where he himself will perform that eschatological role—perhaps at this time becoming one with his heavenly double, now that his earthly sojourn has ended […] No passage requires that one think of a separate being called the son of man existing in heaven while Enoch lives elsewhere. Enoch sees the son of man in visions of the future, not in disclosures of the present. He is seeing only what he will become.91

In Ethiopia a further step was taken, in that the Son of Man identified as Enoch was, in Ethiopian traditional exegesis, further identified as Jesus Christ.92 This brings us to the third suggestion. Grant Macaskill has recently offered a sophisticated theological understanding of this issue that aligns closely with the traditional Ethiopian understanding.93 The result of this essay is as follows:

… Macaskill proposes that the identification be understood in terms of the Christian theological tradition that deploys the imagery of ascent into heaven and identification with Jesus in relation to the final end of Christian life. “Enoch remains Enoch as he is identified as the Son: he does not become, simply, Jesus.” This solution contributes to Christian theology in two ways. First, it takes us back to a pre-Enlightenment yet challenging notion of the person whereby my whole identity, the entirety of myself, might be constituted by the personhood of another. Secondly, it provides a different slant on salvation history. Enoch, the seventh patriarch after Adam, participates in the identity of the Son of Man despite the fact that he died long before “the Christ event,” the period of earthly Incarnation. To understand this we must do (what the Ethiopian Church does) and introduce a framework that is at home in older readings of scripture “but alien to much modern discourse, one that starts with the being of God, now understood in terms of the Incarnation, and understands all in this light.” 94

The identification of Enoch with the Son of Man in 71:14 is not, however, the end of the story. For the Head of Days then proceeds to describe the exalted status and role that he will have in relation to the righteous thereafter (71:15-17). This includes the following:

And all will walk on your path since righteousness will never forsake you; and with you will be their dwelling and with you, their lot, and from you they will not be separated forever and forever and ever (71:16).

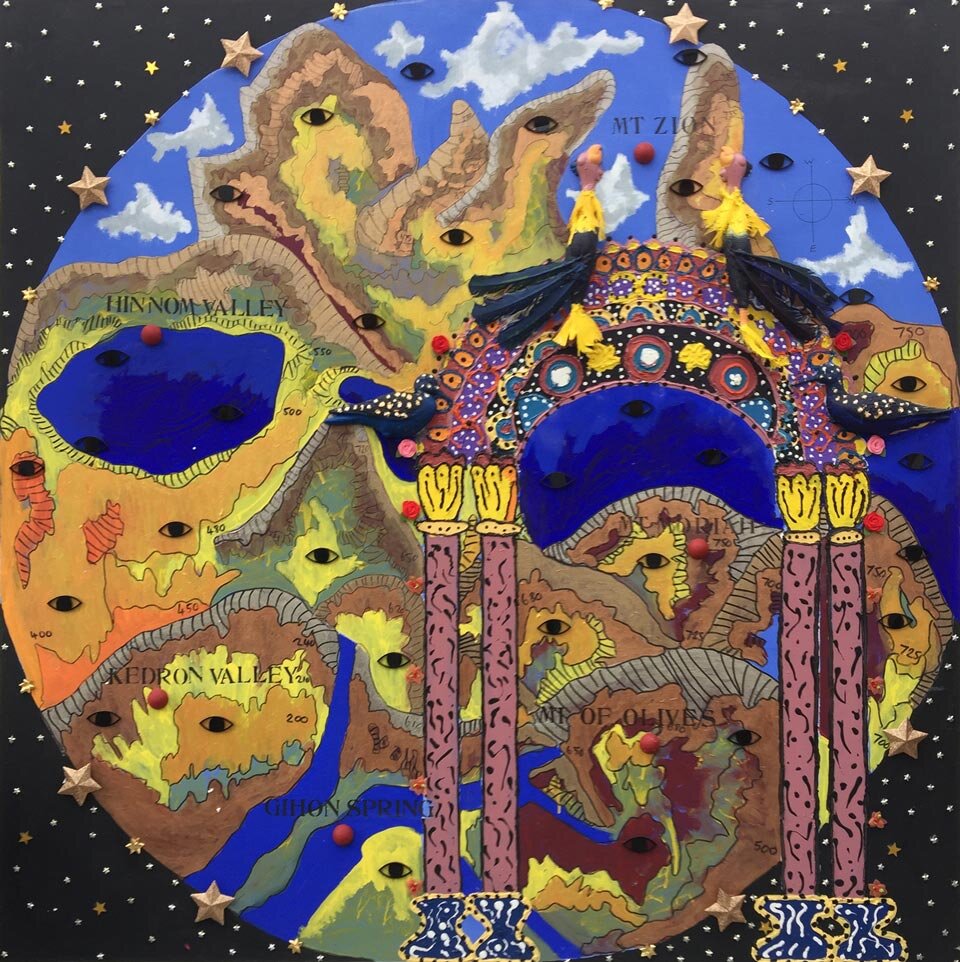

In the painting the artist has chosen to represent the entirety of Enoch’s transformation in 1 Enoch 70-71, which, as we have seen, begins with an allusion to Gen 5:24 that moves beyond the account in 1 Enoch 14 by introducing the Son of Man and culminates with the identification of Enoch as the Son of Man in 71:14 and the description of his exalted status thereafter (71:15-17). Like many painters in the late Medieval and early Renaissance pictorial tradition, the artist has incorporated the passage of time onto the canvas by depicting Enoch at two stages of the process. In so doing, he depicts Enoch at his most human and vulnerable but also at his most spiritual, as the Son of Man, on whom righteousness dwells. We watch him coming from a prostrate position into the act of ascension and then transformation. The first stage shows us a contemplative Enoch, half in prayer and half in readiness for his entire body to transform. The viewer looking on and wondering how this must feel realises that it is not a sensation of pain but one of ecstasy. For this, the artist has drawn inspiration from the Bernini sculpture St Theresa in Ecstasy in the Santa Maria Della Vittoria Church in Rome.

Enoch’s expression is one of deep contemplation. He is in a meditative state, staring at the earth, surrounded by flora and fauna encompassing the planet. Enoch kneels on a bed of flowers to show how deeply he is in touch with and imbedded within the earth, an earth that earlier in the text cries out at the indignities that are being visited upon it (1 Enoch 9:2). The fact that he is leaving the earth’s globe and moving into a celestial atmosphere underlines that something magnificent is happening and that at the same time God is performing an act of kindness and generosity. Not only will Enoch be taken up to heaven alive and saved from the destruction of the earth at the End-Time, his real identity and ultimate destiny as Son of Man will be revealed, as the one with whom the righteous will dwell forever.

We see that Enoch’s face is beginning to turn upwards—a metaphor for his spirit moving towards God. His writing paraphernalia, for he is God’s heavenly scribe after all, is also floating as if to transcend time, and suggesting that Enoch will continue to write and be a conduit to help humanity understand Gods’ wisdom through his text. Although Enoch is dressed in a humble manner, a halo of ladybirds and golden energy surrounds him as he is about to become the Son of Man.

The next stage of his ascending shows Enoch’s face looking down on himself as he is transformed. He will soon pass through the ice circle into heaven and his expression is therefore of extreme contentment. At this point Enoch is beginning to enter the flames that surround God (his face reacts accordingly). This is a direct artistic response to the description in the text that all his flesh melted (71:11). Four archangels watch as God, as white as snow, and Michael oversee his ascension and transformation. The two golden Nagars also look on in order to record the whole process.

Umbrellas are traditionally used in Ethiopian funerals, where they are highly respected religious objects and regarded as a sign that the Holy Spirit is present. Priests often read at a funeral service with an umbrella above their heads to demonstrate their closeness to God. The two umbrellas in this painting are thus a celebration of Enoch’s ascension and an indication that God himself is overseeing the process.

Finally, it is significant that Enoch’s image is once again made by a face print. The starting point of a human face being transformed is central to the process of the entire painting, as it represents the idea that humanity can be saved and that God will transform the righteous.

How the exhibition has been received

Afterword

__

88 See Darrell D. Hannah, ‘The Elect Son of Man and the Parables of Enoch’, in ‘Who is This Son of Man?’ The Latest Scholarship on a Puzzling Expression of the Historical Jesus, Library of New Testament Studies, Larry W. Hurtado and Paul L. Owen (eds) (London: T & T Clark, 2011), 130-158.

89 T. W. Manson, ‘The Son of Man in Daniel, Enoch and the Gospels’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library (1949-195) 32: 171-195, at 189-190.

90 Ibid., 186.

91 James C. VanderKam, ‘Righteous One, Messiah, Chosen One, and Son of Man in 1 Enoch 37-71,’ in The Messiah, (ed.) J. H. Charlesworth (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 1992),169-191, at 184.

92 See M. A. Knibb, ‘The Translation of 1 Enoch 70:1: Some Methodological Issues’, in his Essays on the Book of Enoch and Other Early Jewish Texts and Traditions (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 161-175, at 173.

93 Grant Macaskill, ‘The Identity of the Son of Man: Messianism and Participation in the Book of (1) Enoch’, in Esler, The Blessing of Enoch, 133-146.

94 Philip Esler, ‘Introduction’, in Esler, The Blessing of Enoch, 1-14, at 11.