Enoch Writes the Watchers’ Petition by the Waters of Dan

(1 Enoch 13:4-7)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

The process of writing occupies a prominent role in 1 Enoch 1-36. This theme begins in the section dealing with the rebellion of the Watchers (1 Enoch 6-11) when God tells Raphael to write all Asael’s sin ‘on (or over) him’ in 10:8. This presumably involves Raphael writing an epitaph over Asael’s tomb or an indictment for use at the final judgment.57 Although this is the first of a number of occasions when angels engage in writing, the main character to do so is Enoch himself, who is presented as a scribe.

Enoch had been translated to heaven before the secession of the Watchers from heaven and had spent his time with the Watchers and the holy ones (12:1-2). But after the Watchers descended to earth and created havoc there, the good angels sent him to earth to warn them that they would not receive forgiveness and would even witness the slaughter of their beloved sons (the Giants; 12:1-6). In some Ethiopic versions of 1 Enoch 12:3 (perhaps translating now lost Greek versions) Enoch says that the Watchers ‘called me, Enoch the scribe’. This was a self-designation by Enoch indicating that he regarded being a scribe as a fundamental aspect of his identity; it was how he categorised himself.58 In the next verse the good angels directly addressed him in this way, saying, ‘Enoch, righteous scribe, go and say to the Watchers of heaven—who forsook the highest heaven …’. Yet their mission for Enoch did not involve his use of scribal skills. Instead, they commissioned him to deliver a message of condemnation that he would relay orally to the rebellious Watchers (12:4-13:2). This he did (13:3), his status as righteous presumably qualifying him to deliver such a message to those who self-evidently were not. The condemned Watchers asked Enoch to employ his scribal skills in writing a memorandum of petition for them seeking forgiveness and then reciting this petition before the Lord of heaven (13:4-5). Enoch wrote out this petition for them and then went off the waters of Dan, south of Mount Hermon, to recite it to God (13:6-7). Later, God himself called Enoch and said, ‘Fear not, Enoch, righteous man and scribe of truth’ (15:1). Various references to this petition in this section of the text consolidate the picture of Enoch as a scribe. Enoch’s scribal activity is not mentioned again until 1 Enoch 33, when Enoch sees the ends of the earth and the gates of heaven from which the stars come forth (vv. 2-3), clearly alluding to the opening verses of the Astronomical Book (1 Enoch 72:1), and writes down what Uriel shows him (33:4). This statement legitimates the role of Enoch as the scribe who communicated astronomical knowledge to the Enochic scribes in the third century BC to the first century AD, that is, to those who claimed intellectual descent from him.

That Enoch is presented as a scribe in this text and in the other constituent parts of 1 Enoch, when the Hebrew Bible says nothing about him in such a role, means that some, if not all, of the other members of the scribal group who produced 1 Enoch over three or four centuries were also scribes. Why would the author of 1 Enoch 1-36 have designated a hero, a revealer of heavenly mysteries, from the past, as a scribe if that did not correspond to the self-designation of the members of his group? The presentation of Enoch as both a righteous scribe and someone with cosmographic and astronomical knowledge made him an exemplar for this group and the alleged source of their own writings on the righteous and the unrighteous, and on the nature, history and ultimate destiny of both humanity and the cosmos itself.

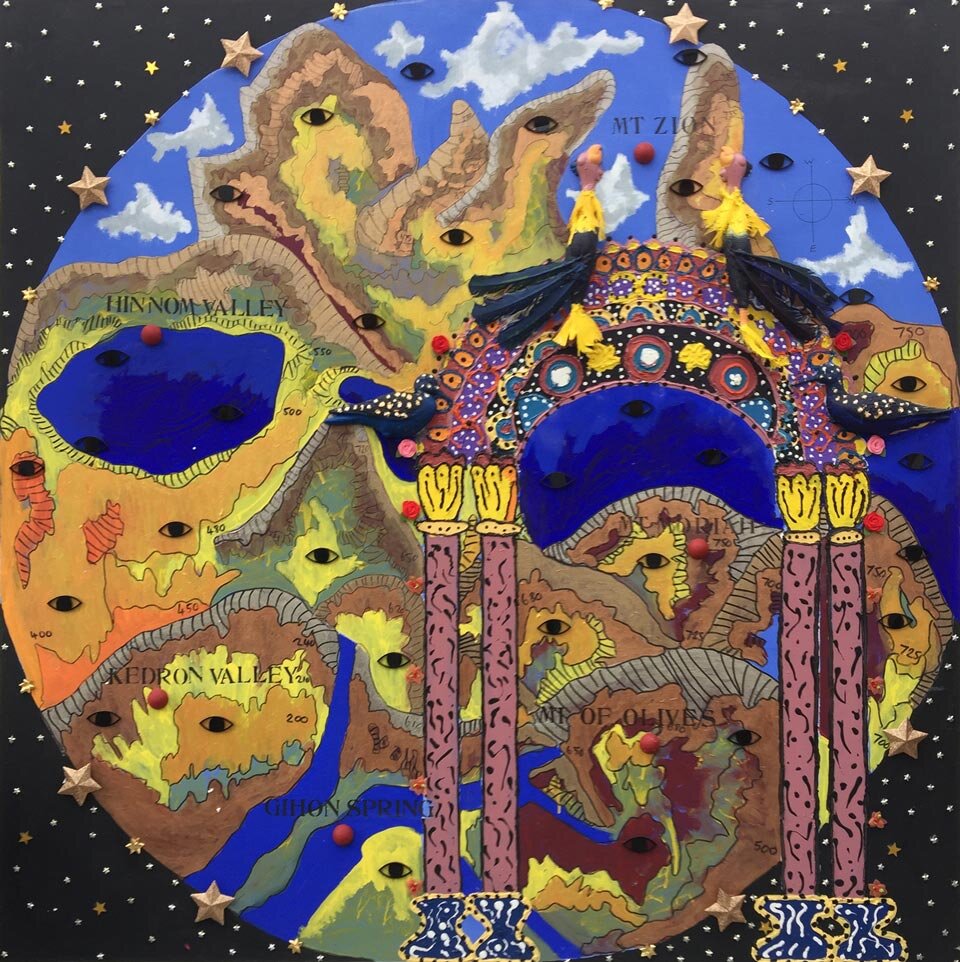

This painting was inspired by an image in an illuminated manuscript that the two authors saw in the Abba Garima monastery in northern Ethiopia in 2017. The artist has sought to depict Enoch in the actual act of scribing and here we see him writing out the petition to God as he sits by the waters of Dan. The text on the parchment, in Ethiopic, is a quotation from 1 Enoch 13:6: ‘Then I wrote out their petition and the requests concerning themselves, with regard to their individual deeds, and concerning their sons for whom they were making request, that they might have forgiveness and longevity’. The petition will be submitted to God in his heavens on behalf of the fallen Watchers. But Enoch has had a vision in his sleep and has been shown the judgement God has decided upon for the Watchers. The fish symbolises Enoch in this visionary state; it jumps out of the water as a celestial advocate, sent to support him.

The angels are trapped within ‘the valleys of the earth’ (1 Enoch 10:12) awaiting their judgement. We can foresee their fate as Enoch is surrounded by the Dudael rock formation that will also entrap Asael (1 Enoch 10:4-7). The fallen will be held within the prison until the End of Days and the ultimate judgement. God’s guardians are in attendance, not only in the kingdom of heaven but also in the form of the two birds, representing good angels, who look on in order to observe and be messengers to God. The ancient Nagar is also present, symbolising the recording of text for the 1 Enoch version of events. We see the Ethiopian cross and the ladybird halo around Enoch’s head as he scribes. This portrays his destiny, indicating that he will become a prophet and walk with God for eternity.

The painting process is again post conceptual in essence, taking both the original text and the painted illumination as the starting point. The figure used to portray Enoch was achieved by printing real clothes. The process of building up the painting was accomplished by taking different events from the original text in order to create a composition. The finished painting is multi-layered, with many dimensions of meaning. The audience should view this painting in sequence with the other 11 paintings in order to see the linear dialogue.

On to the next painting?

The Imprisoned Angels

__

57 Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch, 222.

58 For a discussion of Enoch as a scribe and the scribal group responsible for 1 Enoch, see Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers, 153-187.