Enoch’s Journeying to the Ends of the Earth

(1 Enoch 33-36)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

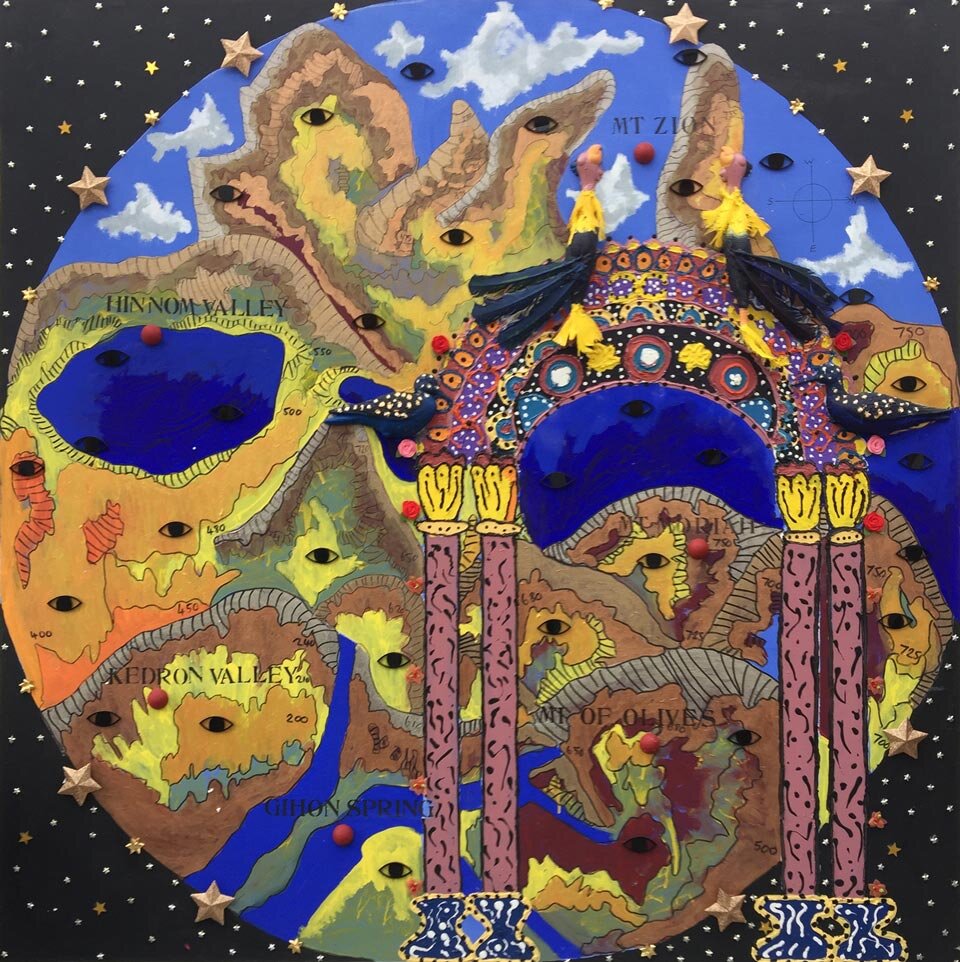

The painting, Enoch’s Journeying to the Ends of the Earth (1 Enoch 33-36), focalizes Enoch as learned in cosmography, especially astronomy, an area of knowledge that formed the original interest of the Enochic scribes. The second half of the Book of the Watchers, the name often given to 1 Enoch 1-36, is taken up with journeys to different parts of the cosmos that Enoch undertakes with heavenly guides (Chapters 17-36). Enoch’s second journey, comprising 1 Enoch 20-36, runs, broadly speaking, from the western boundary of the earth to its eastern boundary. This section of the work begins with a list of the seven angels who accompany Enoch and interpret what he sees (1 Enoch 20). It continues with Enoch visiting locales associated with natural, angelic and human history: the place of punishment for disobedient stars (21:1-5); the prison of the fallen angels (21:7-10); and the mountain of the dead, where the spirits of sinners will be held and punished (22). After witnessing the fire that runs around the west of the earth (23), Enoch continues to travel through places that have had or will have a major role in human salvation: the mountain of God and the tree for the righteous at the End-Time (24-25; Painting 9); the site of Jerusalem (26; Painting 10) and the place of eternal punishment (27); and the Paradise of Righteousness (28-32).

A change comes in Chapters 33-36, for here Enoch visits (in what for us is a counter-clockwise direction) astronomical features, in the form of the great wonders at the ends of the earth. We must bear in mind that Enoch envisages the earth as a huge disk and around its perimeter ‘the heavenly canopy rests like an inverted cup on a saucer of the same diameter’,84 and that there are gates in that canopy on the four sides of the earth. From these gates the stars emerge and he writes down their number, names, positions and courses as Uriel explains them to him (33:3-4). In particular, Enoch observes the three gates that exist on each of the four sides— north, west, south and east. Winds issue from the gates to the north and south (34 and 36), there are more gates on the western side (35), while on the east are the small gates from which the stars appear and then proceed westward (36:2-3), presumably to disappear into the western gates.

The original and primary interest of the scribal group that rallied under the banner of Enoch, probably in the third century BCE, was a form of astronomy with a notably Babylonian cast. Such astronomical knowledge was already out of date compared with Greek astronomy by the third century BCE,85 but these scribes continued to treasure it as their intellectual tradition, probably because their ancestors had acquired it during Israel’s exile in Babylon in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. This fairly primitive astronomical lore is the subject of 1 Enoch 72-82, usually called the Astronomical Book or the Book of the Luminaries. As a means to propagate this learning and to express their views on other matters, especially God’s role in salvation history, these scribes chose a venerable figure from the past who might become their revered spokesperson. This was Enoch, recorded in the Old Testament briefly but potently in Gen 5:18-24. Enoch no doubt suggested himself because the number of the years during which he was on earth before God took him—365—was equal to the number of days in a solar year. Moreover, the fact that he had been taken to heaven while still alive (Gen 5:24) and was presumably still there meant that he must have been privy to secrets on a cosmic scale—an extraordinary knowledge of the universe. Enoch claims to have seen and to have recounted to the group through this text things that no other human had ever seen (19:3). Specifying Enoch as their source and eponymous hero, therefore, made the claims of these scribes credible and elevated their social status.

The heavenly gates mentioned above are a fragment of the astronomical knowledge that the Israelite ancestors of the Enochic scribes must have brought back from exile in Babylon in the sixth or fifth centuries BCE. 1 Enoch 33-36 were possibly written as a linking summary to the much more extended treatment of the courses of the sun, moon and stars, and the emergence of the winds, through the heavenly gates fulsomely described in the Astronomical Book (1 Enoch 72-76).87

Through this painting the artist has sought to illustrate how Enoch had the great advantage of being given by God and the angels the opportunity to survey the celestial universe because of his elevation to heaven while still alive (Gen 5:24). In this section of the text Enoch is journeying across the universe with the archangel Uriel. Enoch, who, unlike Uriel, is noticeably without wings, is nevertheless able to fly or levitate into this celestial landscape, previously unknown to humanity.

This is the beginning of Enoch’s transformation to becoming God’s scribe. He has a golden hue about him and wears a wooden orthodox Ethiopian cross symbolising his pure yet earthly status. The angel Uriel is a far more dominant figure. He spreads his domestic wings and wears a silver Ethiopian cross to suggest his celestial status. This is his domain and he is about to share the secrets of the heavens. This is an indicator that Enoch, having once recorded this information, will be confirmed in his place to walk with God. Enoch is eager to learn and to discover the truth. He is in a place between heaven and earth, a transformative space that allows him to realise the full magnitude of God’s work and power and to realize, in his honour and awe of God’s creation, that his role is to praise this great work.

The portals, represented by mirrors, are symbols of the gateways into other parts of the celestial universe. Not all that Enoch witnesses is beautiful; some of the scenes fill him with dread. By the artist’s use of the mirrors, the viewer can observe their own significance reflected back onto themselves as well as reflecting the environment in which the painting is shown. The original plan, frustrated by Covid-19, was to exhibit the paintings in Gloucester Cathedral in May 2020 (and again in Canterbury Cathedral September 2020), so that architectural homage to God would be reflected and thereby become part of the painting.

The landscape is fantastical with the mountain ranges described in the text like nothing on the earth. Could one of them be God’s seat from where he looks down on humanity and passes judgment? The space is not meant to be either beautiful or abhorrent. It could be both or neither; it is purely fantastic. The ring of silver stars reveals that both our travellers, Enoch and Uriel, are about to pass through the clouds and out into God’s territory, the solar universe. Yet the painting leaves the viewer to wonder and ponder the impossible possibilities of what will happen next.

This is a self-reflecting and contemplative painting, charged with endless potential for one’s self.

On to the next painting?

Enoch’s Transformation Before the Angels and God

__

84 Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1, 330.

85 VanderKam, Enoch, 92; Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers, 179-180.

86 Jonathan Stock-Hesketh, ‘Circles and Mirrors: Understanding 1 Enoch 21-32’, Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 21 (2000), 27-58, at 28.

87 Stock-Hesketh, ‘Circles’, 34.