The Earth Cries Out

(1 Enoch 7:6)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

Not just human beings but also the earth itself suffered because of the violence of the Giants. Not only did they devour the natural products that human beings produced and kill and devour the people themselves, but they ‘began to sin against (that is, devour) the birds and beasts and creeping things and the fish’. They even devoured one another’s flesh and drank the blood (7:3-5). As a result the earth, both a victim of and a witness to immense violence, then acquired personhood and became an actor itself in the drama, since it ‘brought accusation against the lawless ones’ (7:6). This means it ‘petitioned’ heaven, using a standard term for appeals to Hellenistic officials or monarchs. 41 In a later section of the text, the Animal Apocalypse (1 Enoch 85-90), which tells the whole story of humanity (Israel especially) in terms of an allegory involving animals, this feature is described as follows: ‘And again I saw them (i.e. the Giants), and they began to gore one another, and the earth began to cry out’ (87:1). We have here, accordingly, the powerful notion of ‘the cry of the earth’, which is now an expression regularly used in environmental circles to describe the earth’s response to the devastation and degradation that human beings are wreaking upon it. Ethiopian theologian Daniel Assefa has noted that since the expression ‘the cry of the earth’ has been taken up as a motif in today’s environmental theology, this brings home the relevance of 1 Enoch to modern theological discussion. He observes that in 1 Enoch human beings were not responsible for the injury suffered by the earth: the ‘initiative came from angels, children of heaven, but the consequences became terrible for the children of the earth.’ But it ‘is not so with the role of human beings today. The rapid degradation we see is attributed to imprudent human action that has taken place during the last two hundred years or so.’ 42 Yet whether from angelic or human causes, the earth cries out, a powerful idea first articulated in 1 Enoch.

The complaint or cry of the earth in 7:6 is matched a little later in the text by a similar cry from human beings themselves. For here it is reported that ‘the voice of those who were perishing went up to heaven’ (8:4). Heaven’s receipt of this petition is described in a remarkable scene set first on the battlements of heaven and then in some room within:

Then Michael and Ouriel and Raphael and Gabriel looked down from holy heaven and saw much blood being poured out upon the earth. Having gone inside, they said to one another, ‘The voice of those who are crying out on earth has reached the gates of heaven’ (9:1-2). 43

Thus the earth and its human inhabitants share the same suffering at the hands of the Giants and exhibit the same response, a cry to heaven. A profound solidarity exists between a suffering earth and a suffering humankind.

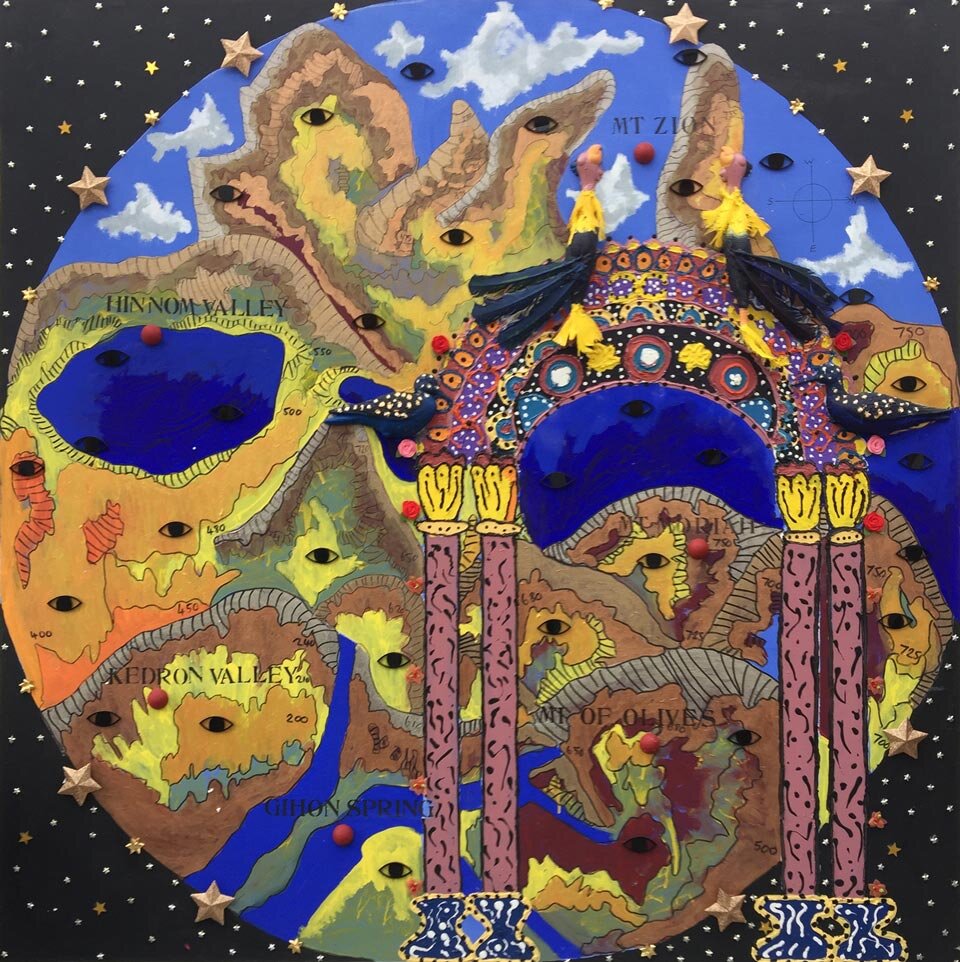

In the painting, The Cry of the Earth (1 Enoch 7:6), we view the earth from the perspective of Enoch as he wanders through the celestial atmosphere. Enoch observes the earth from within the knowledge limitations of his own era, not yet fully formed and with only a basic understanding of landmass, the oceans, and how they are linked together. But as a heavenly wanderer, he can see the earth not only spatially but also across time: he is able to survey three separate stages of earth's evolution progressing into the future, and can therefore foresee how humanity will neglect and slowly destroy the earth.

The three separate globes in the painting are Enoch's view of these three phases of earth's ecological history, as he floats above with the privileged view not only of a celestial traveller but a time traveller. The first earth, which surrounds the other two, is painted in a deep Prussian blue to depict our world at the time of the great deluge. Here the earth is drowning and all existence is submerged. We recall that humanity had an opportunity after the Watchers had imparted their knowledge, but subsequent choices ultimately led to humanity’s destruction, save for the survival of Noah and his family. The array of flora and fauna submerged beneath the surface serve as a reminder of the disastrous consequences of these actions.

Over time, a second earth was formed. It is left unclear what particular era is represented here but it could be contemporary. Although the earth is still fertile it has been infected with a virus and there are poison mushrooms sprouting across the lush green surface. We are looking through ash clouds, a pointer to our nuclear age and the destruction that has caused. The sea is deep ultramarine in colour and its surface is partly frozen. We are seeing here the advent of globalisation and the beginning of earth's deterioration. We can recognise in the final phase the reason that we have fallen into this plight.

The third, golden earth symbolises the dominance of wealth, power, knowledge and ultimately greed over everything else. Even the infected mushrooms are now covered in gold. The atmosphere has been destroyed as the clouds have become golden lumps of glistening mass. There is nothing good remaining. There are no human beings and no humanity. Ethiopia is the crucial central focus of this painting. An Ethiopian Orthodox cross at the centre serves to draw the viewer's eye to that location. The shape of the country is picked out in red and Calla Lilies (the national flower) grow out to form a mouth with a tongue. Ethiopia itself therefore becomes the actual mouthpiece from which the agonised screaming described in the book of Enoch is coming. There is, however, a glimmer of hope in the antlers that burst through the surface. Although they represent death (a trophy which celebrates killing for its own sake) they are piercing the greed of the gold and returning to their natural state, like arms reaching out to the heavens. This is a positive sign as it shows earth calling out to the creator for help. We can hope that nature will survive although all seems lost; that it will reassert itself.

The viewer is given the same perspective as Enoch, looking down as if from heaven. We cast our eyes down upon the three cycles of the earth, with the two earths in the middle of the painting. On the left we look through grey clouds, and on the right golden, glistening clouds as everything in earth’s atmosphere is affected. We see not only what Enoch has recorded in that moment, but also what humanity has done and will do. Enoch celebrates nature and wants it to reassert itself so that utopia can exist once more.

The painting's message is optimistic: if we learn from our mistakes and obey basic principles then ultimately the world can recover. This is nature's distress signal—the earth crying out.

On to the next painting?

God on His Throne

__

41 Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers, 72-78.

42 Daniel Assefa, ‘The Cry of the Earth in 1 Enoch and Environmental Theology’, in Esler, The Blessing of Enoch, 124-132, at 131. For another essay on the text and ecological issues in the wider biblical context, see Loren T. Stuckenbruck, ‘Words from the Book of Enoch on the Environment’, in Esler, The Blessing of Enoch, 111-123.

43 Translation by Philip Esler.