The Imprisoned Angels

(1 Enoch 10)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

The earth’s cry of distress, the subject of Painting 4, The Earth Cries Out (1 Enoch 7:6), reached the gates of heaven, where Michael, Sariel, Raphael and Gabriel, heard it and also the souls of human beings raising their petition:

Bring in our judgment to the Most High, and our destruction before the glory of the majesty, before the Lord of all lords in majesty (9:3).

These four archangels responded by reminding God of what was happening on earth, caused by the Watchers taking human wives who produced Giants who ravaged the earth and by the revelation of secret knowledge by Shemihazah and Asael that caused iniquity everywhere (9:4-10). At the end of their address they actually complain that, although God knows all of this, he has not given them instructions to do something about it (9:11)! Perhaps stung by this rebuke, God issues instructions in turn to each of the four archangels: he sends Sariel to Noah with instructions on preparing for the coming flood (10:1-3); he orders Raphael to deal with Asael, with a subsidiary injunction to heal the earth (10:4-8); he directs Gabriel to kill the sons of the Watchers, presumably meaning the Giants (10:9-10); he tells Michael what to do in relation to binding Shemihazah and the other Watchers, as well as killing the Giants (10:11-15); and, finally, he gives Michael another commission, that of renovating the earth (10:16-22).

The dramatic date for this narrative is shortly before the events of the flood and its aftermath (Genesis 6-9). In the biblical chronology, the survival of Noah and his family would lead to another period of human history, in which wickedness would again become rampant and which would end with the Last Judgment when God will finally deal with evil.59 This broad timetable of salvation, to which the author(s) of 1 Enoch fully subscribed, determined the punishment God prescribed for the rebellious Watchers, who were immortal, since it meant providing for the two relevant periods, between the flood and the Last Judgment and then from the Last Judgment onwards. The means chosen by God was to constrain them under the earth until the Judgment and then to consign them to the eternal fire of punishment.

Asael is singled out for special treatment. Although he shared in the Watchers’ common enterprise of descending to earth to take human wives, which led to the birth of giants who ravaged the earth, he compounded his sin by teaching humanity forbidden technology, which comprised ‘eternal mysteries that are in heaven’ (9:5) (see Painting no. 3, ‘Asael Teaching Metalwork (1 Enoch 8:1’). Raphael was instructed to bind him, cast him into darkness and put him under60 sharp rocks in the wilderness of Dudael until the final judgment when he would be led away to the burning conflagration. Just as the Enochic scribes had inherited astronomical law from Babylonia gained during the period of Israel’s exile there in the sixth century BCE, the details of Asael’s punishment may ultimately derive from punishment prescribed for witches in Babylon.61 Immediately after these instructions concerning Asael, God instructed Raphael to ‘heal the earth, which the Watchers have devastated’, an instruction without particulars yet given in such close proximity to the detailed punishment of Asael as to raise the question of whether the two events are to be seen as connected.62 As for Shemihazah and the other Watchers, God tells Michael that when they have seen their sons perish, he is to bind them in the valleys of the earth, until the day of judgment when they will be led away to the fiery abyss, to imprisonment and eternal torture.

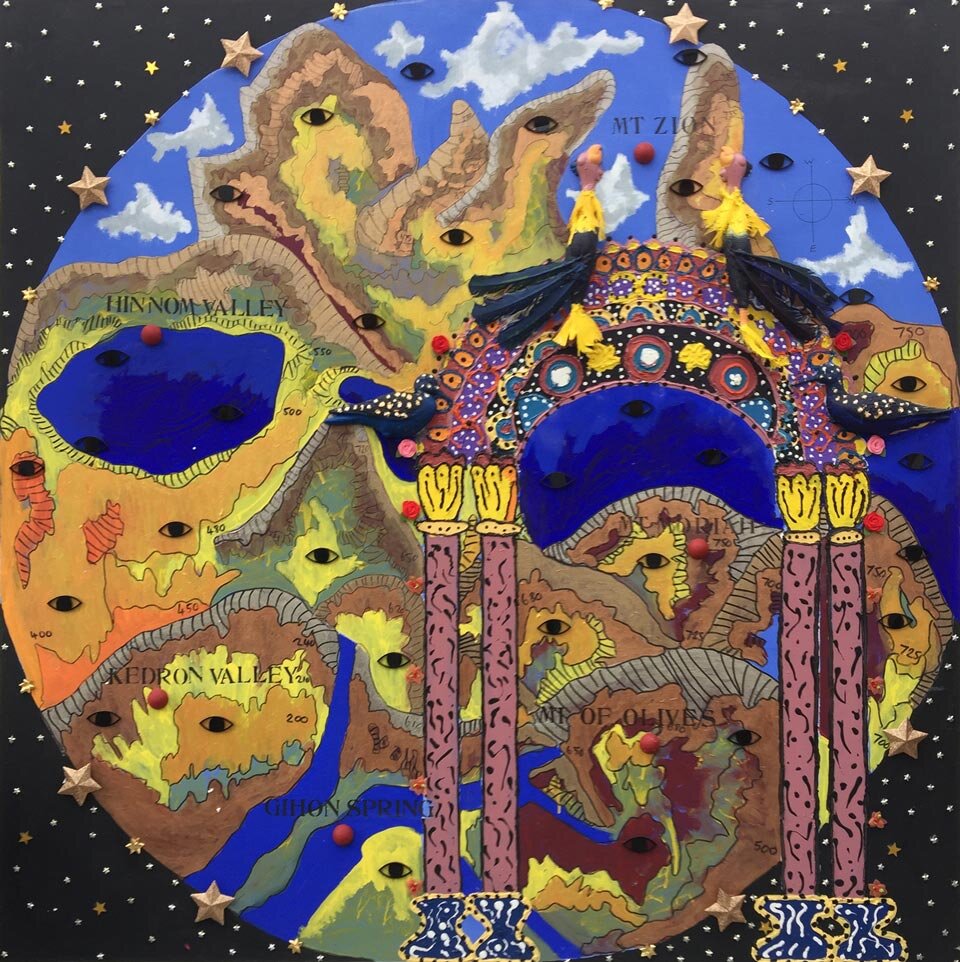

Of the two descriptions of the punishment of the Watchers in the text (10:4-8 and 10:11-13), the artist has chosen in his painting to focus on the former, when Raphael, having bound Asael hand and foot and cast him into the darkness—meaning (in the artist’s conception) blind-folding him—carves an opening in the desert in Dudael and throws him there, covering him with sharp stones. Within the painting we see Asael still in the form of a golden angel, no longer beautiful but not quite human. He still has his angel’s wings but his facial expression shows that he has lost God as his saviour and has forfeited his angelic rights as he is made to suffer in a penal manner. His liberty and position must be sacrificed as punishment. The desert here is a ring made of sand and we see that snakes are beginning to enter the ring to encircle Asael. On the dark sand beetles, cockroaches and a giant scorpion begin to gather as if a plague is upon him.

Asael is beginning to sink into the rough and jagged rocks of Dudael; terror is all around him. Within moments he will be engulfed in darkness and no light will be able to enter. He will remain there till judgment day, when he will be cast into the fire to help in healing the earth. The theme of these rocks is echoed throughout the series as a vision of what is to come. The pain and suffering are apparent in the red rocks that symbolise earth and the destruction of humanity, because Asael taught them secrets from heaven. The ecological dimension asserts itself, as the devastated earth—its hilly peaks like an agonised mouth—cries out (the subject of a later painting in the series), with the punishment of Asael functioning to aid its regeneration.

The two Nagars bear witness, so that all generations will know what happened here. The two angelic birds are Watchers who remained loyal to God, overseeing the event in order to report to God that his instructions have been successfully carried out. Flies buzz around Asael’s head as if he has become infected by what he taught human beings. The red glass jewels represent payment in rubies like a dirty manna from heaven—as if he was receiving ironical payment for his actions. They also represent the blood of humanity, forever soaked in the earth as a reminder of his sins against God. This depiction is a brutal reminder that everyone (even the Watchers) can be punished by God for their sins. This scene will float eternally through the universe within a celestial bubble until the End Time.

The artist has used a human impression to depict Asael as not-quite-human, not-quite-angel. The Rocks are real and represent the brutality of our servitude. The colours act out the pathos of the situation, what one has given up for a lustful act—an act against God. The Ethiopian cross bears witness to the event, so that this story is not lost to the world but can be reclaimed by scholars years later.

On to the next painting?

Abel’s Cry for Vengeance on Cain

__

59 On evil and God’s response to it in 1 Enoch, see Esler’s essay, ‘Deus Victor’.

60 Here we follow the Ethiopic text; the Greek version has Asael placed on top of sharp rocks.

61 See Hendryck Drawnel and Henryck Drawnel, ‘The Punishment of Asael: (“1 En.” 10:4-8) and Mesopotamian Anti-Witchcraft Literature’, Revue de Qumrân Volume 25 (2012), 369-394.

62 Adolphe Lods, Le livre d’Hénoch: Fragments grecs découverts à Akhmîm (Haute-Égypte) publiés avec les variantes du texte éthiopien (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1892), 118.