God on His Throne

(1 Enoch 14:18-21)

By Philip Esler and Angus Pryor

In 1 Enoch 14, Enoch has a vision in which he is carried to heaven. Having passed through the outer wall of heaven, built of hailstones with circling tongues of fire, Enoch crosses a space and approaches a building that turns out to be God’s palace. 44 It has a smaller antechamber, and adjacent to it, and visible through a door, lies a much larger room in which God is seated on a throne. Here is how Enoch describes it:

I was looking and I saw a high throne, and its appearance was like ice, and its roundness was like the shining sun, and the border was cherubim. And from underneath the throne flowed forth rivers flaming with fire, And I was unable to see. Upon it sat the Great Glory; His garments were like the appearance of the sun and whiter than abundant snow. No angel could enter into this house and gaze on his face Because of the splendour and glory, And no human being was able to look at him (1 Enoch 14:18-21) 45

For some reason, commentators regularly (and grievously) mistranslate the third statement as ‘and its wheels were like the shining sun’, even though the Greek word for ‘roundness’ (τροχός; trochos) is in the singular (as is the word kebab, also meaning ‘roundness’, in the Ethiopic translation) and later in the text, at 1 Enoch 18:4, the same words in Greek and Ethiopic are used of ‘the roundness of the sun’. 46 It is not surprising that the scribe or scribes responsible for 1 Enoch 14, originating in a tradition with a strong interest in astronomical phenomena, 47 should hit upon the sun, with the perfect roundness of its form, as providing a model for the divine throne. The sun-like roundness of God’s throne co-exists with imagery that paradoxically combines ice and rivers of fire. Later we learn that certain angels did approach God (1 Enoch 14:23), although we do not know how close they came.

Underlying this image is the notion, quite common in the Hebrew Bible, of God on his throne in heaven. In 1 Kings 22:19, for example, the prophet Micaiah is quoted as saying: ‘Therefore hear the word of the Lord: I saw the Lord sitting on his throne, and all the host of heaven standing beside him on his right hand and on his left.’ Even earlier than this and possibly influencing the picture was the council of the gods depicted in the Ugaritic documents from Ras Shamra and other Ancient Near Eastern representations of divine dwellings. In Psalm 45:6 the psalmist proclaims that ‘Your divine throne endures for ever and ever,’ while Psalm 103:19 states that ‘The Lord has established his throne in the heavens, and his kingdom rules over all.’ In Isa 6:1-6 the prophet recounts a vision he has of the Lord sitting on the throne, but it is situated in the Temple. Above God stood the seraphim, each with six wings, with one calling to another, ‘Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory.’

Yet the picture in 1 Enoch 14:18-21 is very different from these. Above all, it features the elaborate imagery of sun, ice and fire mentioned above, the product of a powerful visual imagination at work in the writing. Secondly, the Enochic God is located in splendid isolation from both angels and human beings in a manner not evident in the other texts. In 1 Enoch God is alone in the room. Only his most senior courtiers approach him. This seems to reflect the total isolation that the Persian kings (beginning with Deioces) introduced into their dealings with their subjects. 49 God’s house in 1 Enoch 14 is like the palace of an Ancient Near Eastern or Hellenistic king; it bears no relation to the architecture of the Temple in Jerusalem.50 The angels in heaven are portrayed like courtiers, not priests in a Temple. When we try to imagine God on a throne we are making an assumption of a monarchical political organisation. We are attempting to understand the unknown in terms of the known.

Much closer to 1 Enoch 14 is the description in Daniel 7:9-10:

As I looked,

thrones were placed

and one that was ancient of days took his seat;

his raiment was white as snow,

and the hair of his head like pure wool;

his throne was fiery flames,

its wheels were burning fire.

A stream of fire issued

and came forth from before him;

a thousand thousands served him,

and ten thousand times ten thousand stood before him;

the court sat in judgment,

and the books were opened (RSV).

Although God is not isolated as in the Enochic version, we do have imagery of flames and a stream of fire. And this throne does have wheels. Yet we must remember that the Enochic passage in question (like the whole of 1 Enoch 1-36) was likely to have been written in the third century BCE or even earlier, while the account in Daniel probably dates from the second century BCE. Accordingly, while Daniel 7 has probably drawn upon 1 Enoch 14 for some of its imagery, the wheels under the throne do not have an Enochic origin. Instead, they were probably inspired by the wheels in Ezekiel, where they are attached, it should be noted, not to God’s throne (which always remains above the firmament in heaven) but to the mobile conveyance that conveys an hypostasis of Yahweh, not Yahweh himself, to various places.51

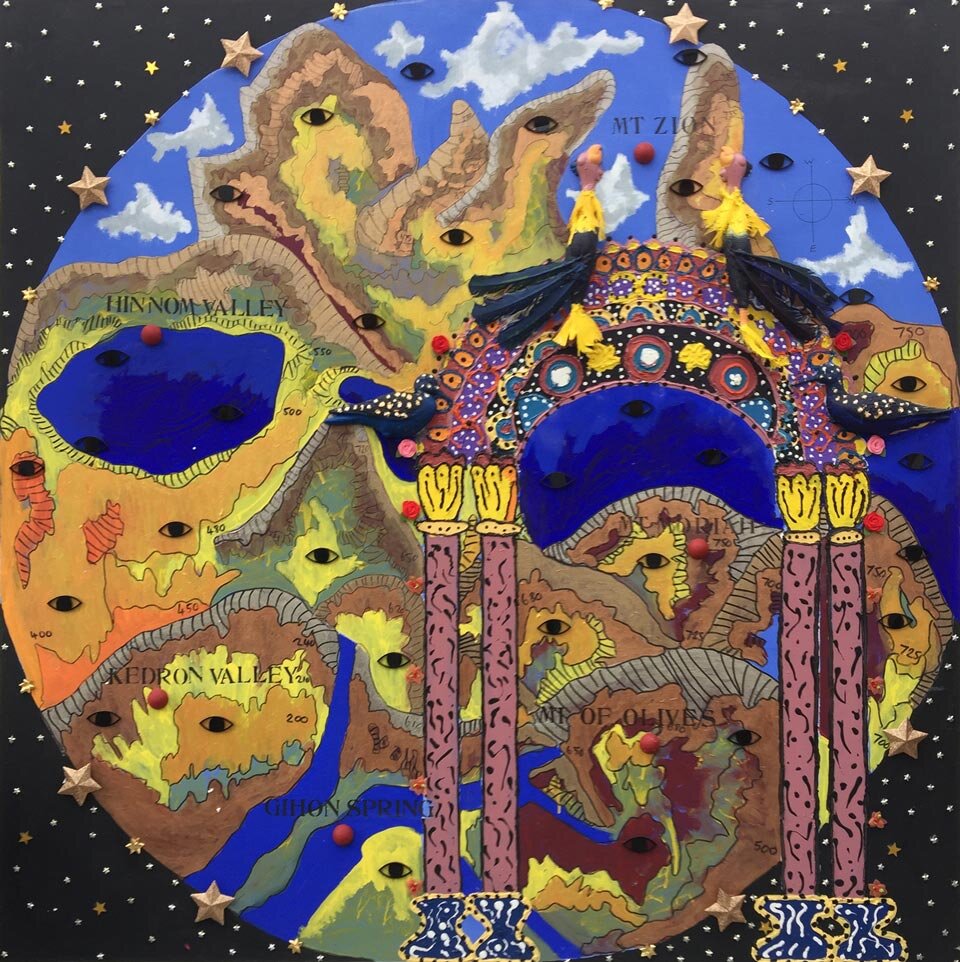

With these textual details in place, we turn to the painting, God on His Throne (1 Enoch 14:18-21). The artist has approached the text within the overall painterly tradition or approach of post-conceptualism that characterises the rest of his oeuvre.52 In addition to painting in oil on canvas, the artist applies ready-made objects to the painting. In these paintings he has also applied prints from objects such as the human face, dolls, fruit and birds to create images in paint on canvas (thus re-appropriating the ready made into the made). Once pressed into the canvas they describe and signify the language and history of painting. With marks placed together both of the imprinted and the gestured, the process of their realisation disappears and all that is left is the language of painting. The artist introduces objects to create a surface tension so that the real, the imagined and the made create a new dynamic and new dimensions. The finished paintings are discursive narratives that explore text, theology and painting as their nascent foundation.

In taking on the challenge of painting God on his throne in 1 Enoch 14, of creating an image of God, based on that text, the artist faced three primary difficulties: firstly, there was the need to be respectful of the text; secondly, the work had to be developed in a painterly manner in line with historic tradition; and, thirdly, it had to be painted with one eye on the Ethiopian tradition of ecclesiastic imagery. Within the text, God on his throne is a visual joy but creating a realized image from a well-read and identified text can have its issues. Faced with translating text into a visual representation, the artist decided to employ a conceptual framework using the ready-made to deliver the image. In this way, instead of drawing or (painting) an image he translated the image via a human body print, using the biblical notion of God creating humanity in his own image (Gen 1:26-27). This painting is therefore an image of a man (literally a full-face print) made by the ‘creator’ in his own image. Like the other three paintings, it is characterised by a two-dimensional presentation—that is, painted as a flat image— in a deliberate evocation of the Ethiopian painting style. In addition, the composition and color derive from traditional Ethiopian paintings, and have then been developed with an eye to Ethiopian tradition to create a contemporary metaphor. It also deliberately captures the naïveté of Ethiopian painting in details such as the large black eyes of God, with a sideways gaze. These eyes also evoke the eyes of Ethiopian prayer scrolls,53 which have a precise apotropaic function.

Scale was essential for this painting since the composition is located in the celestial; the figure of God therefore needed to appear both life-size and infinite at the same time, with proportions and perspective simultaneously intrinsic and extrinsic, thereby creating a micro and a macro effect. This leads the viewer to reflect on more than one level. Firstly, there is an image of God on the human scale and a reflection on humanity. Secondly, we have an unworldly image situated in infinite space, to be imagined rather than directly observed.

The spherical character of the painting is important. This pictorial quality ultimately depends upon the point made above, namely that the Enochic text is speaking not of a wheeled throne but of a throne characterised by roundness, that very word later being used of the sun (1 Enoch 18:4; 72:4) and the moon (1 Enoch 73:2). This roundness entails that there is no top or bottom, so ultimately no hierarchy as with the sun itself, meaning we see God in perpetual motion and that he does not move but all move around him.

The composition thus deals with the spherical, with God sitting or floating on his throne surrounded by the paradoxical and implausible notion of fire and ice. The throne in the painting is an impossible structure. It is painted as a ball of energy, almost like a spiro graph, or something that is in perpetual motion, but also as a dichotomy giving energy as it rotates through the celestial atmosphere, even though the painting is static. The celestial space that the God of the throne inhabits sits within a non-descript space. This links back to the journey of Enoch, firstly when he is taken around the heavens and then when he is translated to be with God (1 Enoch 14:8; 70). The space it evokes is the attempt of a mortal who looks up into the night sky with wonder and tries to locate the place where God sits. The painting describes this space as being everywhere; it is a universal space. The little gold spheres are wheels within wheels. The artist is trying to show God’s energy, with its greatness created through the image where one element is added to another. It is similar to the combination of fire and water as an antithesis to each other, but also as a requirement for sustainability. The artist creates a painting depicting God’s machine for creation, much like a living cell!

The other significant compositional factor is that the roundness attributed to the throne in 1 Enoch 14:18 now corresponds to the fact that so many Ethiopian churches are constructed as circles within circles.54 The circle of the painting is like the floor or the ceiling of the church; so that the painting is like a plan or a schematic of the space. Architecture infuses aesthetics. Because of the three circular zones of many Ethiopian churches, to encounter church art you have to make a circular journey through rather dark space. This is Iike encountering a disk or entering an orb. Just like a saint or angel features a halo or nimb, this painting has the essence of the spherical. In part, the painting halos God, replicating Ethiopian pictorial methods of representing sanctity. In some ways the painting is like a visualisation of belief; it is like seeing God. The nature of God’s gestures is also one of ambiguity. The visualisation here is a form of visual exegesis where the artist interprets and expands the Enochic text. Gesture is important; there is a frontal, full-face God, with his eyes looking to the viewer’s right (thus representing a good person in Ethiopian iconography) as he surveys his infinite kingdom. His open hands suggest that he is a welcoming God who is transcending the visual space as if moving towards us so that we can embrace him and what he stands for.

The birds above God’s shoulders act as cherubim who are the guardians—the Watchers. They are hybrids from the pure birds from the Bible (Deut 14:11) and the fact that they are golden suggests that they are other-worldly or Watchers (Angels) who act as guardians looking at God. The colors are taken from the cherubs found in Ethiopian churches and so become not only the guardians of the Holy of Holies but also the guardians of Ethiopian culture. The blue and brown shapes evoke Ethiopian cherub wings visible in the ceilings of some Ethiopian churches, such as those in the Dabra Berhan Selassie Church in Gondar. The Ethiopian cross on the left and the orb on the right symbolize the Holy Trinity.

The colors in the painting are charged with metaphor and meaning. The God figure is dressed in traditional Ethiopian ecclesiastical clothing, which is white and therefore understated and pure. Hanging around the neck of God is a traditional Ethiopian cross in the Lalibela style, of unpainted wood but colored gold to show the significance of the wearer. The coloration of the rays round God link directly to the colours of Ethiopia visible in paintings in the Cathedral in Addis Ababa and around the Tomb of Haile Selassie. They feature constantly in paintings of the Holy Trinity. The two modified deer-heads are a reference to 1 Enoch 90:38, where an animal of uncertain identification but great importance is mentioned. It is called a nagar. What kind of a creature is a nagar? Francis Watson has noted that this Ge‘ez term means ‘word’ or ‘speech’, though it is not the equivalent of logos and has no clear Christological connotations. He has noted that according to an old and attractive theory, this Enochic animal came to be known as a ‘Speech’, nagar, because of a double translation failure. On this view, the Greek text underlying the Ge‘ez, transliterated the Hebrew word r’ēm, a wild ox, as rēm, which the Ethiopic translator misread as rēma, word. Whether this explanation is correct or not, the Enochic bestiary now includes the great-horned nagar, which is said to enjoy first place among the white bulls. This is the impressive white creature on the right of an image from the Garima III Gospel Book.55 The Garima Gospels being very early translations into Ge‘ez, with illuminations, that survived in a monastery in northern Ethiopia.56 The artist’s inclusion of a reference to the nagar of 1 Enoch 90:38 serves to integrate the picture of God on his throne in 1 Enoch 14 with the wider narrative of the text, and its happy ending for the just.

Finally, the image is insouciant as to whether one is a believer or an unbeliever. In either case, one is drawn to this image of 1 Enoch 14:18-21 like a moth to a shining light, as one sees God in a burning celestial place surrounded by ice. Intellectually, the artist knows that it is sublime and one always wants to transgress into the sublime, which is faith. The painting creates a narrative using the image of God as human being and human being as God. But once it is finished, it is no longer an illustration. It becomes an entity. One looks at it and asks, ‘What is God?’ It points beyond imagery of God to the essence of God at work throughout the cosmos. It is, paradoxically, both apotropaic and welcoming. In this painting the artist has responded directly to the theology in the text and attempted to replicate it.

On to the next painting?

Enoch Writes the Watchers’ Petition by the Waters of Dan

__

44 The discussion of this painting is gratefully reproduced by permission of the Biblical Theology Bulletin, Volume 50:3 (August 2020), 136-153, in an article entitled ‘Painting 1 Enoch: Biblical Interpretation, Theology, and Artistic Practice’, by Philip Esler and Angus Pryor.

45 Translation by Philip Esler.

46 Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers, 131-135.

47 James C. VanderKam, Enoch and the Growth of an Apocalyptic Tradition. CBQ Monograph Series, 16 (Washington: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1984), 76-109.

48 E. Theodore Mullen Jr., The Divine Council in Canaanite and Early Hebrew Literature. Harvard Semitic Monographs 24 (Chico, CA: Scholars, 1980); Michael B. Hundley, Gods in Dwellings: Temples and Divine Presence in the Ancient Near East. Writings from the Ancient World Supplement Series (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013).

49 Esler, God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers, 46-47, 68.

50 Esler, ibid., 136-152.

51 John T. Strong,‘The God that Ezekiel Inherited’, in Paul M. Joyce and Dalit Rom-Shiloni (eds.),The God Ezekiel Creates. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 607 (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 24-57, at 33-40.

52 On post-conceptual art, see Jason Gaiger, ‘Post-Conceptual Painting: Gerhard Richter’s Extended Leave-Taking in Themes in Contemporary Art’, in Gillian Perry and Paul Wood (eds.), Themes in Contemporary Art (London: Yale University Press, 2004), 89-135; and Alexander Alberro and Sabeth Buchmann (eds), Art After Conceptual Art (Cambridge, MT: MIT Press, 2006).

53 On Ethiopian prayer scrolls, see Jacques Mercier, Art that Heals: The Image as Medicine in Ethiopia (New York: Prestel and The Museum for African Art, 1997) and Esler, Ethiopian Christianity, 152-157.

54 Esler, Ethiopian Christianity, 162-165.

55 Francis Watson, ‘Enoch and the Fourfold Gospel: Decoding an Ancient Image’, paper delivered at a conference of Ethiopian, British, European, North American and South African researchers on 1 Enoch and contemporary theology in the University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham in October 2015.

56 Esler, Ethiopian Christianity, 103-106.