Afterword

by Martin O’Kane

This refreshingly new, stimulating and hugely attractive exhibition, Enoch: Heaven’s Messenger, is part of an exciting and welcome project that brings together two topics about which most of us, regrettably, remain woefully ill-informed and unenlightened:

the Book of Enoch and the cultural sophistication of Ethiopia.

That 1 Enoch is not included in the canon of the Old Testament has meant that, unlike the rest of the Old Testament, its contents do not adorn the walls of major galleries in the West while, for the majority of people, the distinctiveness of the place and function of religious art in Ethiopia is either unacknowledged or, more often, simply completely unknown.

There may indeed, as Philip Esler points out in this catalogue, have been a multitude of scholarly books, articles and essays published on 1 Enoch, but how far have these impacted on the wider public? What this exhibition and its informative catalogue have spectacularly achieved is to entice the viewer into the complex, unknown and mesmerising world of Enoch, a world of enigmatic visions, mysterious figures, angels and demons and which challenges us to reflect on universal themes of good and evil and the hopeful possibility of redemption. The exhibition thus achieves what Philip Esler argues is lacking in existing Enoch scholarship, namely an appreciation of the book’s role in theology, a lacuna that has been, for centuries, imaginatively addressed in Ethiopia’s use and interpretation of the book.

The project and exhibition are clearly the result of painstaking and meticulous research, close observation of how religious paintings were displayed in Ethiopia and – most of all – fruitful collaboration between a biblical scholar, Philip Esler, and a practising artist, Angus Pryor. In this, they have paved the way for others to follow. For several decades now, biblical scholars have been documenting how artists have often been keen interpreters of the Bible, but their approaches have been predictably Western and their repertoire of painting generally limited to the Italian Renaissance or seventeenth-century Dutch artists. This project heralds a much-needed new approach, imaginatively going far beyond the accepted Western canon of biblical books and beyond Europe to focus on Ethiopian art. Unlike ‘biblical’ paintings in Western galleries which can be rarely viewed in their original settings (they have been moved from churches or other locations where their original contexts bestowed on them their meaning and significance), this exhibition fully acknowledges and explores the importance of the Ethiopian church setting, the context in which religious themes are interpreted and represented in Ethiopian art. The exhibition, through its construction of a model Ethiopian church, mirrors the way paintings are hung there –not in any strict sequence but simply as part of the whole narrative. Thus, there is no one way to interpret the twelve large canvasses in this exhibition: viewers can create their own itinerary through the exhibition in a multitude of ways.

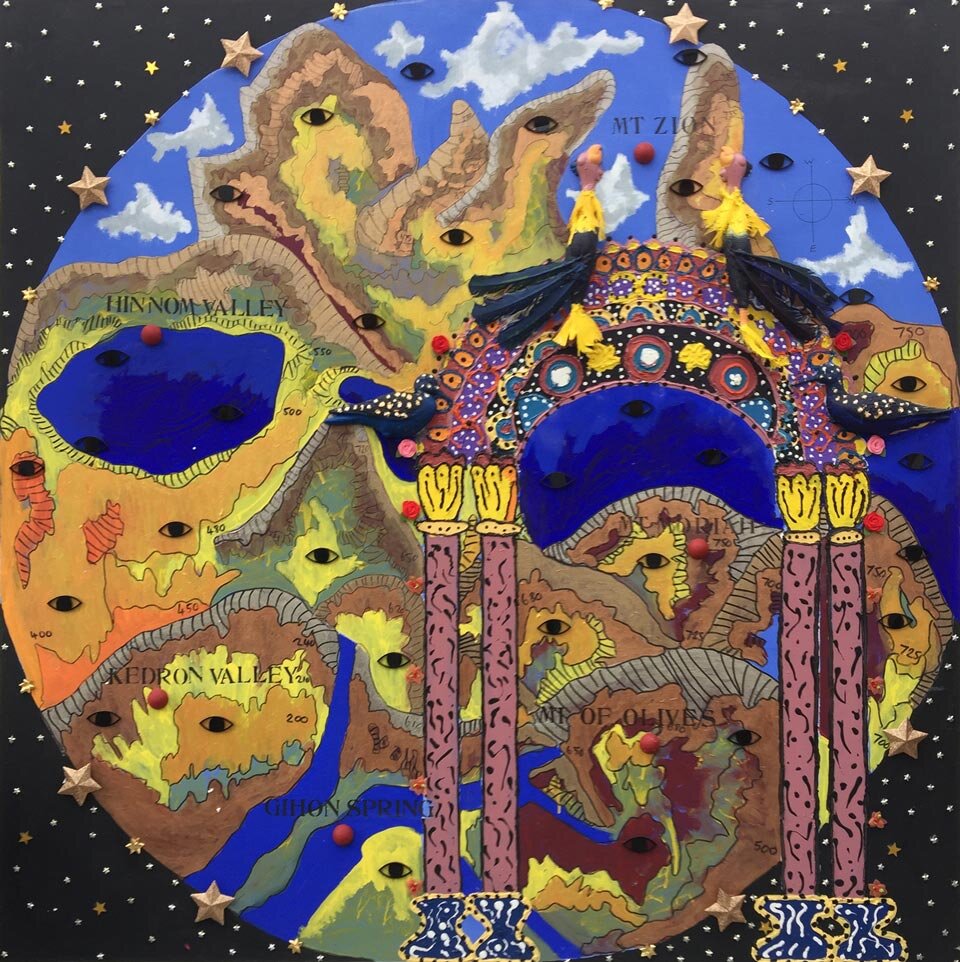

The scope and sheer size of the paintings, enhanced by this unique setting, will undoubtedly provide a spectacular experience for the viewer and each one will have his or her own favourite. I, personally, was especially struck by three themes: the first was the motif of the deer antlers that occurs in a number of the paintings; second was how the important aspect of topography was represented; and third, how the enigmatic character of the Watcher Asael was conceived. Entering the exhibition, no viewer can fail to be struck immediately by the antlers that dramatically spring out of the canvas in Painting 1 (God and the End-Time Punishment)—they invade the viewer’s space and draw him or her powerfully into the narrative. The antlers represent the ancient Nagar, a mysterious creature mentioned in 1 Enoch 90:38, but they also act as a reminder of the presence of Enoch, heaven’s messenger, who tells the story and brings it to our attention. The antlers appear as a thread through several of the paintings, each time with a slightly different and intriguing significance; ever-present, they link the paintings to the larger structure of 1 Enoch. Another theme imaginatively represented is the importance of topography –in relation both to Ethiopia itself, as well as to Jerusalem, that all-important mythological and religious centre of the earth. In Painting 4 (The Earth Cries Out) Ethiopia is the crucial central focus and an Ethiopian Orthodox cross at the centre serves to draw the viewer's eye to that location. The shape of the country is picked out in red and Calla Lilies (the national flower) grow out to form a mouth with a tongue. Ethiopia itself, therefore, becomes the actual mouthpiece from which the agonised screaming described in the book of Enoch is coming. In Painting 10, the artist represents the topography of Jerusalem described vividly in 1 Enoch 26-27. He imaginatively sets the scene as a vision, and paints the city not merely defined and constrained by its mythical past but introduces motifs that recognize its importance in the future beyond Enoch’s description of it. Finally, I was very much drawn to Painting 3 (Asael Teaching Metalwork), because of its striking contemporary relevance to our ever-increasingly violent world. The painting focuses on Asael (a leader of the Watchers) teaching humankind new knowledge. He appears on the left of the painting as a golden angel painted in a recognizably Ethiopian style, with coloured wings. Asael taught human beings ‘to make swords of iron and weapons and shields and breastplates and every instrument of war. He showed them the metals of the earth and how they should work gold to fashion it suitably, and concerning silver, to fashion it for bracelets and ornaments for women’ (1 Enoch 8.1). Theologically, this painting explores, in a very powerful and shocking way, how good and creative powers can be manipulated for evil ends.

In this ground-breaking exhibition, Angus Pryor and Philip Esler have led the way for others to follow and there are, indeed, many directions in which their insights can be expanded to explore other topics, or included in existing topics to give them an added rich dimension. For example, as well as Enoch, the story of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba have been given a very distinctive Ethiopian flavour in the fourteenth‐century epic Kebra Nagast (Glory of the Kings), used to validate the claims of the Ethiopian Solomonic dynasty; paintings and frescoes from the life of Solomon adorn churches in Ethiopia, for example, the Church of Dabra Marqos, Goggam where two large murals depict, first, Solomon’s sacrifice at Gibeon and his dream, followed by the proof of his wisdom, his arbitration between the two conflicting women. In addition, this exhibition also contributes to our existing knowledge of iconography associated with the figure of Enoch (in the West, he is generally depicted alongside Elijah who, like Enoch, did not experience death, to typify the Ascension of Christ). Finally, the attributes of the Watcher Asael, inventor of metalwork, are reminiscent of the attributes associated with Idris (Enoch) in Islamic tradition. Idris, regarded as the first teacher in Islamic tradition, communicated to the human race principles of astronomy, geometry, philosophy, mathematics and logic. Additionally, the exhibition will bring to mind many other associations in the area of theology – and for these, both Angus Pryor and Philip Esler are to be warmly commended and congratulated for this unique and spectacular project.

Martin O’Kane

University of Wales Trinity Saint David

June 2020

Want to know more?

Watch interviews with the artists

References

Alberro, Alexander and Sabeth Buchmann (eds), Art After Conceptual Art. Cambridge, MT: MIT Press, 2006.

Assefa, Daniel, ‘The Cry of the Earth in 1 Enoch and Environmental Theology’, in Esler, The Blessing of Enoch, 124-132.

Bachmann, Veronika ‘Rooted in Paradise? The Meaning of the “Tree of Life” in 1 Enoch 24-25 Reconsidered’, Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha (2009) 19: 83-107.

Bauckham, Richard, ‘James and The Jerusalem Church’, in The Book of Act in Its Palestinian Setting. Volume 4, ed. Richard Bauckham. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1995, 415-480.

Bautch, Kelley Coblentz , A Study of the Geography of 1 Enoch 17-19: No One Has Seen What I Have Seen. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

Bredin, Miles, The Pale Abyssinian: A Life of James Bruce, African Explorer and Adventurer. London: Flamingo, 2000.

Brown, David Blayney, Romanticism. Phaidon Art and Ideas. London: Phaidon, 2010.

Charles, Robert Henry, The Book of Enoch. Oxford: Clarendon, 1893.

Charles, Robert Henry, ‘Book of Enoch’, in The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament in English. Volume II: Pseudepigrapha, by R. H. Charles. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1913, 188-277.

Charles, Robert Henry, The Book of Enoch, translated by R. H. Charles, with an introduction by W. O. Oesterley. London: SCM, 1917.

Charlesworth, James H. and Ephraim Isaac, O Livro de Enoque Etíope ou 1 Enoque, trans. Orlando Iannuzzi Filho. Sao Paulo: Entre os Tempos, 2015. Drawnel, Hendryck and Henryck Drawnel, ‘The Punishment of Asael: (“1 En.” 10:4-8) and Mesopotamian Anti-Witchcraft Literature’, Revue de Qumrân (2012) 25: 369-394

Eliade, Mircea, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1959.

Esler, Philip F., God’s Court and Courtiers in the Book of the Watchers: Re-interpreting Heaven in 1 Enoch 1-36. Eugene, OR; Cascade, 2017.

Esler, Philip F., ed., The Blessing of Enoch: 1 Enoch and Contemporary Theology. Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2017.

Esler, Philip F., ‘Deus Victor: The Nature and Defeat of Evil in the Book of the Watchers (1 Enoch 1-36)’, in Esler, The Blessing of Enoch, 166-190.

Esler, Philip F., Ethiopian Christianity: History, Theology, Practice. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2019.

Esler, Philip F. and Angus Pryor, ‘Painting 1 Enoch: Biblical Interpretation, Theology, and Artistic Practice’, Biblical Theology Bulletin (2020) 50:3: 136-153.

Flemming, Johann, Das Buch Henoch: Aethiopischer Text. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1902.

Fogg, Sam. Ethiopian Art, Catalogue 24. London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2005.

Gaiger, Jason, ‘Post-Conceptual Painting: Gerhard Richter’s Extended Leave-Taking in Themes in Contemporary Art’, inThemes in Contemporary Art, ed. Gillian Perry and Paul Wood. London: Yale University Press, 2004, 89-135.

Hannah, Darrell D., ‘The Elect Son of Man and the Parables of Enoch’, in ‘Who is This Son of Man?’ The Latest Scholarship on a Puzzling Expression of the Historical Jesus, Library of New Testament Studies, Larry W. Hurtado and Paul L. Owen (eds) (London: T & T Clark, 2011), 130-158.

Hipp, Elisabeth, ‘Painting from the Galerie Neue Meister at the J. Paul Getty Museum,’ in Ulrich Bischoff, Elisabeth Hipp and Jeanne Anne Nugent, From Caspar David Friedrich to Gerhard Richter: German Paintings from Dresden. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2006, 15-32.

Hundley, Michael B., Gods in Dwellings: Temples and Divine Presence in the Ancient Near East. Writings from the Ancient World Supplement Series Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013.

Ilsink, Matthijs, and Jos Koldeweij et al. Hieronymus Bosch, Painter and Draughtsman: Catalogue Raisonné. New Haven: Yale University Press and Mercatorfonds, 2016.

Knibb, Michael A., in consultation with Edward Ullendorff, The Ethiopic Book of Enoch: A New Edition in the Light of the Aramaic Dead Sea Fragments. Two volumes. Oxford: Clarendon, 1978.

Knibb, Michael A., ‘The Translation of 1 Enoch 70:1: Some Methodological Issues’, in his Essays on the Book of Enoch and Other Early Jewish Texts and Traditions. Leiden: Brill, 2009, 161-175

Lods, Adolphe , Le livre d’Hénoch: Fragments grecs découverts à Akhmîm (Haute-Égypte) publiés avec les variantes du texte éthiopien. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1892.

Macaskill, Grant, ‘The Identity of the Son of Man: Messianism and Participation in the Book of (1) Enoch’, in Esler, The Blessing of Enoch, 133-146.

Manson, T. W., ‘The Son of Man in Daniel, Enoch and the Gospels’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library (1949-195) 32: 171-195.

McKenzie, Judith S. and Francis Watson, The Garima Gospels: Early Illuminated Gospel Books from Ethiopia. Manar Al-Athar Monograph 3. Oxford: Manar Al-Athar, 2016.

Milik, J. T., The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments of Qumran Cave 4. With the collaboration of Matthew Black. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1976.

Mercier, Jacques, Art that Heals: The Image as Medicine in Ethiopia. New York: Prestel and The Museum for African Art, 1997.

Minton, David, in Critical Narratives in Colour and Form (exhibition catalogue), India Habitat Centre, New Delhi, 27–30 November 2012; Curated by Angus Pryor and Text entries edited by Grant Pooke.

Nickelsburg, George W. E. 1 Enoch. A Critical Edition on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia Commentary. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 2001.

Nickelsburg, George W. E. and James C. VanderKam, 1 Enoch 2: A Commentary on the Book of Enoch Chapters 37-82. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012.

Mullen, E. Theodore Jr., The Divine Council in Canaanite and Early Hebrew Literature. Harvard Semitic Monographs 24. Chico, CA: Scholars, 1980.

Paley, Munro D. The Traveller in the Evening: The Last Works of William Blake Oxford: OUP, 2003.

Pooke, Grant, Contemporary British Art: An Introduction. London: Routledge, 2012.

Post-Conceptual Art Practice: New Directions – Part Two, University of Kent Fine Art, 2012.

Pryor, Angus, ‘1 Enoch: An Artist’s Response’, in Esler, The Blessing of Enoch, 191-195.

Rosenthal, Norman et al., eds. Apocalypse: Beauty and Horror in Contemporary Art. London: Royal Academy of Arts Publications, 2000.

Stock-Hesketh, Jonathan ‘Circles and Mirrors: Understanding 1 Enoch 21-32’, Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha (2000) 21:27-58.

Strong, John T. ‘The God that Ezekiel Inherited’, in The God Ezekiel Creates, ed. Paul M. Joyce and Dalit Rom-Shiloni, Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 607. London: Bloomsbury, 2015, 24-57.

Stuckenbruck, Loren T. 1 Enoch 91–108. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2007.

Stuckenbruck, Loren T. ‘Words from the Book of Enoch on the Environment’, in Esler, The Blessing of Enoch, 111-123.

VanderKam, James C., Enoch and the Growth of an Apocalyptic Tradition. CBQ Monograph Series, 16. Washington: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1984.

VanderKam, James C., ‘Righteous One, Messiah, Chosen One, and Son of Man in 1 Enoch 37-71,’ in The Messiah, ed. J. H. Charlesworth. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 1992,169-191.

VanderKam, James C., Enoch: A Man for All Seasons. Studies on Personalities of the Old Testament. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press ,1995.

Watson, Francis, ‘Enoch and the Fourfold Gospel: Decoding an Ancient Image’, paper delivered at a conference on 1 Enoch and contemporary theology in the University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham in October 2015.