Foreword

by Grant Pooke

‘The text deals with fundamental themes of life and death, shame, murder, sin, transcendence, faith and belief. Once an artefact is exposed to an audience and the work is released into the public sphere, it is open to interpretation.’

Angus Pryor, ‘Enoch: An Artist’s Response’, p193, in The Blessing of Enoch: 1 Enoch and Contemporary Theology, ed. Philip Esler, 2017

Visualising apocalypse – whether as divine revelation, cosmological renewal or ideological failure, has a rich and expansive iconography within the history of art. Canonical examples might include the famous Laocoön sculpture (c.27 BCE–68 CE) which depicts the customised punishment meted out to the eponymous Trojan priest (and his sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus), for paternal hubris in defying the gods. Other examples might encompass The Last Judgement (ca.1503–1505), attributed to Hieronymus Bosch. Its triptych format adroitly provides a continuous rather than a monoscenic narrative. The composition depicts paradise and expulsion from the Garden of Eden, the torture and mutilation of the damned with an upper register depicting Christ Enthroned with Saints, signifying the possibility of redemption from sin. 1 Luca Signorelli’s Last Judgement fresco cycle completed for the Capella Nuova of Orvieto’s Duomo (1499–c.1503), visualised scenes from the Book of Revelation. Visceral and compelling in its treatment of the human form in extremis, Giorgio Vasari’s Vite (1550 and 1568) recognised Signorelli’s fresco cycle as one of the achievements of the Italian Renaissance and as a precursor to Michelangelo’s iconic work, The Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel (c.1535–1541).

In the early 19th century, apocalypse as a secularised experience of military conquest and invasion was powerfully memorialised by Francisco Goya’s unpublished series of etchings, the Disasters of War (1812–1815). As David Blayney Brown notes of this response to the French occupation of Spain, ‘…these images of pointless butchery take on a universal resonance that renders questions of personal alignment irrelevant.’ 2 Goya’s graphic and emblematic depiction of divine savagery, Saturn Devouring His Son (1820–23), paradoxically implies a world absent transcendent proposition. A similar negation of the human might be inferred through a reading of several landscape compositions by Caspar David Friedrich, whilst others might be interpreted as offering tantalising glimpses of the divine made manifest through a pantheistic nature. 3

As the world became reified by capital and increasingly atomised human endeavour, there were other, more quixotic treatments of apocalypse, cosmology and redemption. Such were variously explored in work by William Blake, John Martin, Samuel Palmer and, into the 20th century, Stanley Spencer and the Roman Catholic mystic, Eric Gill. More recent art practice has been no less inventive in exploring twentieth century concepts of apocalypse including a series of obsessively-detailed installations by the YBA artists Jake and Dinos Chapman in which the mechanised sadism associated with the ideology of National Socialism was given vivid treatment (Hell, 1998–2000 and 2004–8).4 In recent decades, the west has witnessed forced and often traumatic migrations and diaspora affecting large communities from sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, parts of Asia and the former Balkans. Drawing attention to one aspect of this coercive situation, the mixed-media installation, Dream (2007), by the Yoruba artist from the Republic of Benin, Romuald Hazoumè, depicted the makeshift boats fashioned using plastic oil containers which are launched from the coast of Senegal in desperate attempts by their passengers to reach places of safety and refuge across the Atlantic. Arguably then, within art history and art-making, the subject and re-visualisation of apocalypse is complex. It comprises multiple registers, contexts, authorships and cultural histories which are variously theistic, agnostic or even militantly atheistic.

Enoch: Heaven’s Messenger visualises the narratives, meaning and relevance for contemporary theology of a text, the Book of Enoch or 1 Enoch described by the theological scholar and co-curator, Philip Esler, as ‘the most important ancient Jewish writing not to have been included in the Old Testament.’5 The exhibition had been planned for initial installation at both Gloucester and Canterbury Cathedrals but the Covid-19 pandemic led to the vacation of the scheduled exhibition dates. It comprises an installation of twelve 2m x 2m oil on canvas works and a re-constructed model of an Ethiopian Church by the post-conceptual British painter, Angus Pryor. Each painting depicts an imaginative response and transposition by Pryor of particular parts of the Enochic narrative with detailed iconographical descriptions provided by Philip Esler.

Enoch: Heaven’s Messenger forms part of a larger and ongoing practice as research project which was preceded by an earlier collaboration. In 2015, Pryor curated still small voice: British Biblical Art in a Secular Age (1850-2014), an exhibition of forty art works from the Ahmanson collection at the Wilson Gallery, Cheltenham which included a three dimensional transcription by Pryor of Stanley Spencer’s Angels of the Apocalypse (1949), titled God’s Wrath (2014).

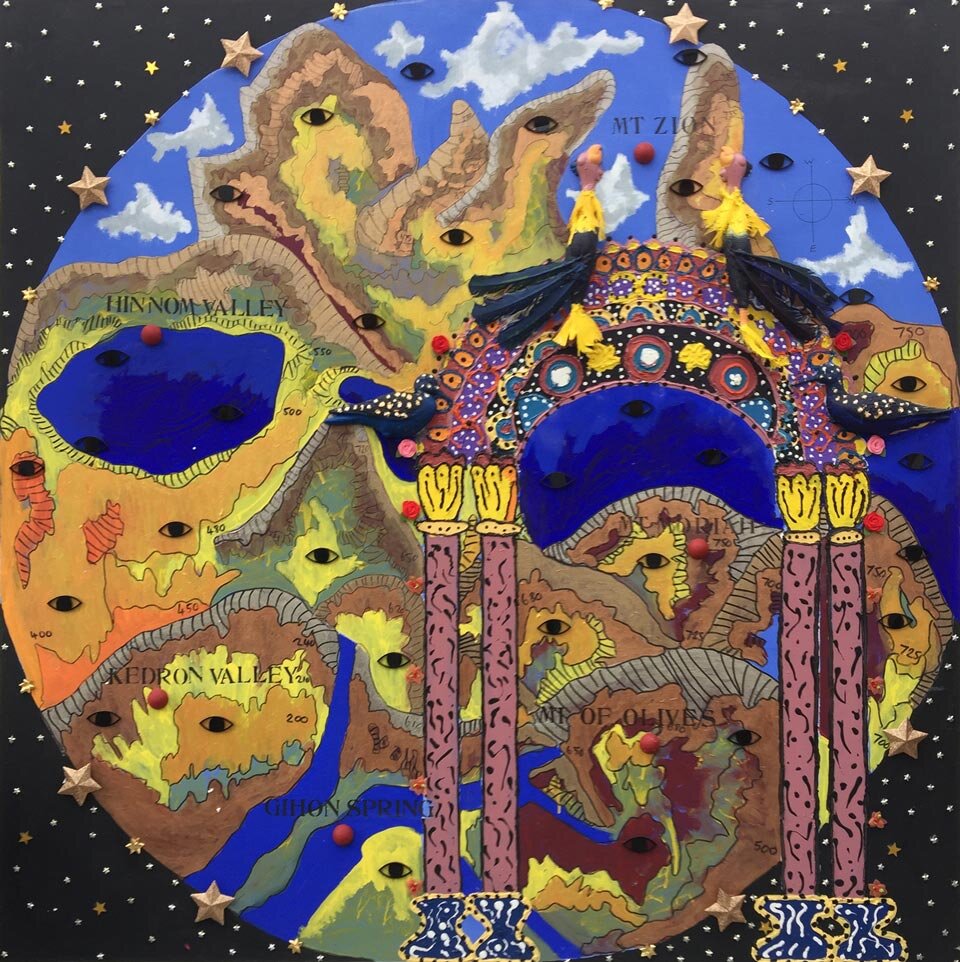

Much of Pryor’s aesthetic melds the gestural legacy of late modernism associated with Philip Guston and Willem de Kooning with the re-introduction of the Duchampian readymade back into the practice of painting.6 His series of twelve oil on canvas images replicate the linear, flat and pared down forms and colour palette associated with Byzantine, Ethiopian and early Coptic Christian iconography.7 Whilst idiomatic and stylistically distinctive, these works are observational and culturally responsive – Pryor has undertaken a series of immersive visits to Addis Ababa, Aksum, Gondar and Lalibela since 2015 in order to experience the cultural legacy of Ethiopian art and architecture at first hand. The painted surfaces include three dimensional objects and imprints – mangoes, lemons, beads, clay depictions of guinea fowl, plastic figurines and deer antlers. Yet despite such relational encounters, these ostensibly narrative paintings are tangibly disjunctive and fugitive of their formal and declared subject matter.

Discussing the kind of abstract and stylised painting he came to favour, the modernist art critic, Clement Greenberg, memorably suggested that it did not have a ‘score’ – recognising not just the highly intuitive and physiological dimension to aesthetic experience, but what he argued was the genre’s intrinsic opacity.8 There are some appreciable similarities here with Pryor’s characterisation of his own painting process:

"There’s a dialogue between the surface and the mark…overpainting…where there’s a line which is definite and then another mark goes on top. It stops it [the painting] becoming an illustration of a mark and starts to be something else." 9

Pryor’s interpretation of the Enochic narrative continues this iterative encounter with painting as post-conceptual mark-making. Throughout these canvases there’s an ongoing tension between mimesis and the medium’s materiality or objecthood. Paint and pigment are typically applied impasto or by syringe, providing as Pryor suggests ‘…a drawn raised property, plastic in origin and with the feel of being sculpted.’ 10 This activation of the picture plane as referentially and conceptually unstable has characterised Pryor’s oeuvre to date.

The exploration of biblical subject matter predates Enoch: Heaven’s Messenger by several years. Pryor’s The Deluge (oil and caulk on canvas, 2007) derived from a visit to Venice and reflection on apocalyptic motifs arising from the Old Testament account of Noah and the Ark. In this composition it is the Ark which is submerged whilst the iconic Adriatic city rests above the waves – a dynamic mediated by a canvas saturated with layers and skeins of crimson and red paint. This is less a maritime vista, but a collision of ideas, an avalanche of pigment of which there are echoes in the colour juxtaposition of crimson and black in God and the End Time (2019/20). As David Minton noted of The Deluge’s chaotic reversal of subject matter:

"The degraded deluge of commodity floats prettily; there is comfort in decadence. Pursuit of pleasure released from moral constraint may be the ultimate freedom. Our desires stare back at us…colours seduce, paint often like skin, unreflective, soft." 11

Due to the present Covid-19 pandemic, the exhibition has been temporarily installed in the white-cube Hardwick Gallery exhibition space at the School of Art & Design, University of Gloucestershire, in Cheltenham. Even encountered virtually, Enoch: Heaven’s Messenger offers a dramatic and immersive viewing experience. Pryor’s sequence of paintings are installed according to a single-line modernist format with a timber reconstruction of an Ethiopian church, designed by the artist, providing the focus for the constellation of paintings. But the exhibition is perhaps art historically singular and exceptional in another regard. There are notable, twentieth century British precedents of painting cycles informed by religious iconography including Stanley Spencer’s iconic canvases at the Sandham Memorial Chapel, Burghclere (c.1923–32), which depict scenes and reflections from the artist’s experience of military service during the First World War. But Enoch: Heaven’s Messenger may be the largest and most ambitious cycle of paintings on a specific biblical text in Britain, possibly since the Reformation.12 As such it is emblematic of painting’s durability as practice, whilst serving to revivify the visualisation of a lesser known religious narrative within contemporary culture.

Enoch: Heaven’s Messenger situates a range of theistic, aesthetic and interpretative concerns relevant to late modernity. Pryor’s visual transcription of the Enochic narrative and its fusion with other western, secular traditions foregrounds contemporary art making as a transcultural practice. The series’ leitmotif is the enclosing circular forms and not infrequent cartographic references – appreciable in Enoch Writes a Petition to God, The Earth’s Cry for Redemption, Abel’s Cry for Vengeance on Cain and The Imprisoned Angels (2019/20). Such are metaphors not just of theistic communion but are variously emblematic of geo-cultural interconnection and an enmeshed humanity.

Grant Pooke

School of Arts

University of Kent

June 2020

Read how it all came together

Introduction

__

1 Matthijs Ilsink, Jos Koldeweij et al. Hieronymus Bosch, Painter and Draughtsman: Catalogue Raisonné (New Haven: Yale University Press and Mercatorfonds, 2016), 290-307.

2 David Blayney Brown, Romanticism. Phaidon Art and Ideas (London: Phaidon, 2010), 106.

3 For a discussion of general iconographical dimensions of these works, see Elisabeth Hipp’s ‘Painting from the Galerie Neue Meister at the J. Paul Getty Museum,’ in Ulrich Bischoff, Elisabeth Hipp and Jeanne Anne Nugent, From Caspar David Friedrich to Gerhard Richter: German Paintings from Dresden (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2006), 19.

4 See for example the broader thematic explored in the Royal Academy sponsored exhibition, Apocalypse: Beauty and Horror in Contemporary Art, edited Norman Rosenthal et al., Royal Academy of Arts Publications, 2000.

5 A technical note and description by Philip Esler sent to the author, June 2020 (unpaginated).

6 See the interview with Mike Walker in Post-Conceptual Art Practice: New Directions – Part Two, University of Kent Fine Art, 2012, 8-11.

7 See for example Sam Fogg, Ethiopian Art, Catalogue 24 (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2005).

8 The observation was articulated in a recorded interview with the art historian T.J. Clark, in ‘Greenberg on Art Criticism,’ recorded for The Open University A315 course presentation, 1981.

9 Studio interview with the author, 10 June 2008. Quoted in Contemporary British Art: An Introduction, Grant Pooke (London: Routledge, 2012), 115.

10 Email from Angus Pryor to the author, 15 June 2020.

11 David Minton, extract reprinted in Critical Narratives in Colour and Form (exhibition catalogue), India Habitat Centre, New Delhi, 27–30 November 2012; Curated by Angus Pryor and Text entries edited by Grant Pooke. Minton’s review and response to Post-Conceptual Art Practice: New Directions – Part Two, University of Kent Fine Art, appeared in Interface, 12 March 2012.

12 This insight and observation was shared by Philip Esler in an email exchange with the author, 18 June 2020.